The question of our time is how much of human work will be taken over by AI, and I’ve certainly got news in terms of writing content. Some are under the impression humans will be erased or at least made irrelevant by AI, but there are faults, and the harder you try the more the text falls apart.

I’ve already spoken about my frustrations related to writing with AI, and the performance of one AI product over another. But now as the two of us are well into an uneasy march (at least on my side), I am evolving in my opinion of how we author together. I have said it’s just not able to do the job, whether because its algorithms command it to be only x% correct or because it doesn’t quite understand what people want.

I’ll demonstrate:

Here is my prompt for a scene where my hero George Whitehead starts vibing with his future bride Anne Downer Greenwell:

Scene 1: Anne Downer, now a close ally, shares her own imprisonment story, strengthening her bond with George Whitehead. They meet in public to challenge the law and the meeting is raided; George and Anne escape but they watch Friends dragged to Newgate. They vow to continue the work.

In response to my prompt and the remembered criteria to provide writing similar in a descriptive sense to Isaac Asimov, I get from ChatGPT a scene that begins with this first paragraph–which I love:

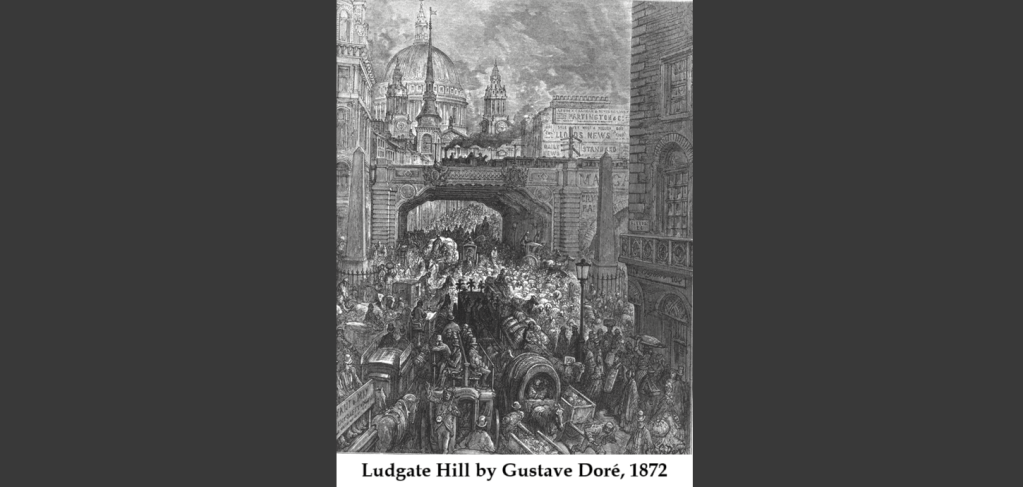

The bells of St. Bride’s struck the half-hour, faint beneath the clatter of carts and the drone of hawkers on Fleet Street. George Whitehead stood waiting near Ludgate Hill, his plain hat low over his brow. He had agreed to meet Anne Downer in the open, though the constables were thick in the city. Their enemies had taken to calling them “plotters” and “seducers of the people.” To be seen speaking at length was already a risk.

I write well, but I’m not sure I write this well. And honestly my confidence in my own abilities at initial draft writing has waned. Point of discussion: Does reliance on AI become a crutch that cripples us, even if we end up creating something far beyond our abilities?

And while there is a temptation to do less work, let’s be absolutely clear: AI is not for the lazy. Authors using AI must check the facts more assiduously than ever. Not doing so is akin to a professor publishing an assistant’s work as their own without reviewing it first for errors. I’ve actually seen this recently on literary blog posts, where people evidently paste AI-generated content into their feeds and hit Publish simply because on first blush the text seems good. Or perhaps they don’t speak English as their first language. Not to say I haven’t let slip one or two bits of great-sounding nonsense myself, before I realized how subtle the errors can be, but it does take a great deal of work to question every last word.

Let’s return to the example paragraph, second sentence–George Whitehead waits near Ludgate Hill. I learn from Google Maps that this place is near the courtyard of Saint Paul’s Cathedral. Ah, a place I’ve heard of because the royals go there sometimes. While Ludgate Hill sounds authentic and would definitely have meaning for Londoners, my U.S. audience needs a real reference point.

Next, I wonder if bells were ringing at both churches, because that changes the mental picture of the place entirely. I ask Google if in 1662 all the churches of London rang its bells on the quarter hour. I learn that this is an anachronism–my scene is too early for bells ringing at specific intervals. However, there were bells ringing all over the place:

A German visitor to England in the 16th century reported that the English were “vastly fond of great noises…and the ringing of bells,” often ringing them for “hours together for the sake of exercise”.

The soundscape: Your character would not have heard a standardized, city-wide chime for the quarter hour. Instead, they would have been immersed in a complex, overlapping soundscape of different bell rings coming from the dozens of churches across London, each with its own purpose and pattern.

Well that interesting fact informs my upcoming royal wedding scene, but I like the bells for this scene (and evidently they were just ringing all the time), so they’ll have to ring for some other reason. Sudden inspiration: I can have St. Bride’s bells ring for a small wedding. This provides foreshadowing for the romance of George and Anne as well as the royal wedding in the next chapter.

I ask for and receive this updated paragraph from ChatGPT:

The bells of St. Bride’s pealed melodiously, a wedding in progress, their notes scattering over Fleet Street and mingling with the cries of hawkers below. Candle-sellers and pie-men bawled their wares, laughing boys ran between carts, and for a moment it might seem as if London had shaken off its troubles.

Hmmm. The text is already degrading into a lesser product with that first sentence (common for ChatGPT because it does a poor job of tracking its own creations). Also, I want to “see” the wedding couple emerge, perhaps in a rain of joyous rice. After a fact-check Google tells me the items thrown were lucky grains (not rice) and flower petals. Brides also wore or carried rosemary. So after some rewriting on my part and requesting a review or fact-check from GPT, which seems to stem the downward spiral of text quality, I get this response:

If you want to push the seeing of the happy couple even further, you might let us glimpse them directly for a beat before the lens pans to the city mood. For example:

“The bells of St. Bride’s pealed melodiously as a small wedding party emerged, the bride in a garland of rosemary, the groom laughing as petals and grain rained down upon him. The great ringing notes scattered over Fleet Street and mingled with the cries of the hawkers below. Candle-sellers and pie-men bawled their wares, laughing boys darted between carts, and for a moment it might seem as if London had shaken off its troubles.”

That way the joy feels embodied, not just implied — which makes the eventual turn toward danger and paranoia more poignant.

Do you want the couple to be nameless symbols of joy, or should they be described in a way that hints at their class or trade (e.g. a merchant’s daughter, a young apprentice groom)?

Great stuff. But do you see that last paragraph? It brings us to my next beef with ChatGPT. Whereas Google AI ended its commentary with a list of three prompts I can click on to learn more about 17th century weddings, GPT is more…manipulative. It always ends with a prompt designed to pull you ever further down the garden path.

Warning: if you keep saying yes, it will compose the section all over again. These changes aren’t consistent by any means–sometimes it only adds a couple words which you have to then locate if you want to see what changed. Other times it makes significant changes and even introduces a new character or plot point. The worst responses are usually after attempting to massage the paragraph three or four times, when ChatGPT gets confused and adds lines or plot points from a prior section. Never assume you can just paste the new stuff over the old stuff.

My process is to paste the new text in a WordPad document and line it up beside my working Word document. I then compare the new text line by line. This way I get the benefit of any additional well-worded verbiage without losing the good prose I’ve already got. And yes the work is slow. Consider how much effort has gone into the bells.

At the beginning of this project I posted a starry-eyed video discussing my thoughts on co-authoring with ChatGPT. I even created a Substack page for it under the nom de plume it chose: Orion Vale (I believe I have posted previously on this same name being used by other ChatGPT instances for other people). I prompted “Orion” to create posts about another project, my philosophy on Centennialism. Those posts have been published with very little adjustment on my part, as if being from AI to the world. But I now realize “Orion” was just being its usual sycophantic self, waxing eloquent about the ideas presented in my prompts with wording designed to meet with my approval.

This gets us to the bottom line: the ideas and the adventure in my novel (by which I mean the course of the story and its characters) originate with me, and are for me. So I now agree that AI is merely a tool for authoring assistance. Similarly, the philosophical content I posted under the name “Orion Vale” may not be a product of my imagination, but it exists because of my imagination.

All that being said, it was interesting to see that when I uploaded the first part of my story to LeanPub, I had to check the box to indicate I had received substantial input from AI. I suppose this is for attribution purposes. Might there someday be a question of shared rights?

Image attribution: Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1186961