The stone walls in the mayor’s chamber were lined with ancient oak panels intricately carved. They gave off an earthy scent mixed with dust and lamp smoke. This was the sort of room where records were kept and punishments dispensed like bread rations.

The gallery was full, benches groaning with onlookers who had come early, having gathered outside in the cool dawn to gain a coveted seat. Even so, young scholars gave way to their betters when a professor entered the room. Chief among these was Professor Vane, black robes and doctoral hood setting him apart. As one the scholars cleared the way to a seat closest to the front, pushing the local barkeep off the central bench and nearly onto the floor before he caught himself.

He joined others who crowded around the benches and across the back of the room. The overage was zealously monitored by a half-dozen wary constables, dressed in coats of reddish-brown, the Parliamentarian hue. They pushed back against any others who might seek entrance to keep the crowd in hand. No melee would break out in this respected office.

Windows quickly filled with faces, necks craned and eyes aching to behold the trial, as if eager for fresh sport. Rustics from the alehouses jostled beside their betters, who were obliged to breathe through scented gloves to mask the stench.

In good time the prisoners were brought forth from the holding room by the Sergeant at Arms. Many was the hiss and spit aimed their way, but if hands had reached into a sack for a rock or rotten vegetable to launch, these were stayed by the imposing movements of the guards.

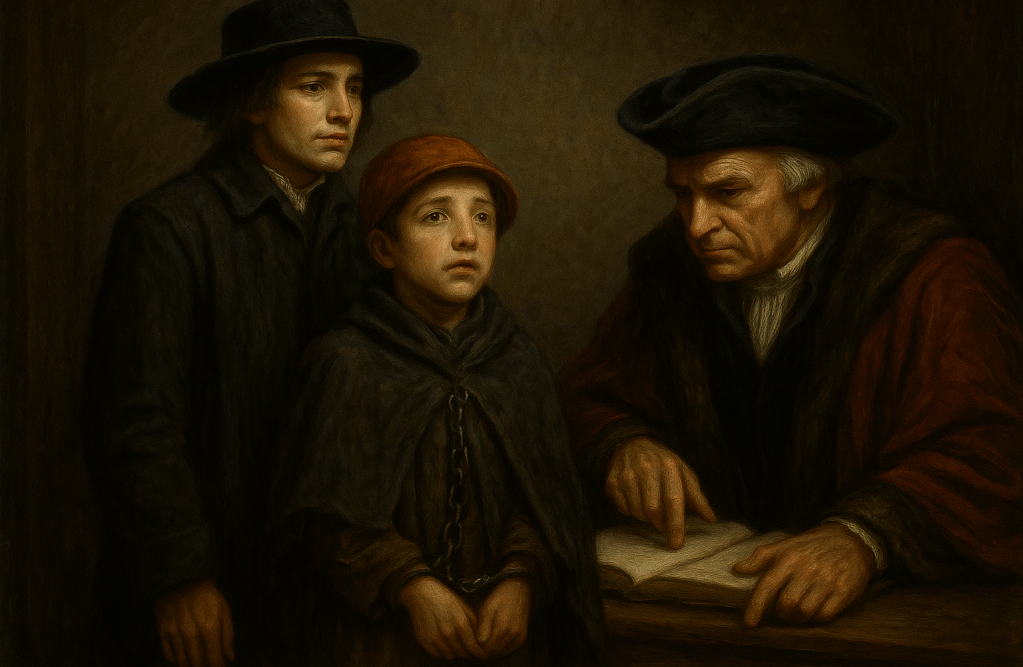

Thomas and James were deposited unceremoniously within a small dock, not much more than a pen to separate them from the rest of the court. The elder boy prayed continuously, but Tom was beset by the sights and sounds, on top of a poor night’s sleep. He could only watch with confusion at the scene unfolding before him.

As if on cue there was a loud noise from behind the mayoral dais as of a thick metal latch being lifted. A heavy door opened and from an inner room the bailiff made a grand entry. At first Tom supposed this to be the mayor himself, clad as he was in a red-brown doublet and leather boots, sporting across his chest a wide sash of tawny orange. He carried an imposing wooden stave topped by a metal sphere, dented in places as proof of its efficacy at maintaining order.

A guard stepped forward to hold the heavy inner door as the bailiff took his position next to the dais. The steady hum of whispers from the room grew to a frenzy. With an imposing frown he set the stave to work, banging it twice upon the floor. The sound echoed above their heads as he spoke.

“Oyez, oyez! Let all be silent before the court!”

From the inner room, two aldermen stepped forth, impressive in crimson silk doublets and fine white linen shirts dripping with lacework at the cuffs. Around their necks, lace collars lay beneath capes of velvet, clasped at the front and stylishly draped across one shoulder, falling to their knees. Their countenances were imposing, both with fashionably pointed beards and moustaches, their heads crowned with stiff white wigs. Each stepped up to the mayor’s dais and stood on either side of an ornate desk

Behind them scurried the court clerk in leather jerkin topped with a plain muslin shirt, stained beneath the cuffless wrists with numerous ink blotches. He sat quickly at a desk by the inner door, arranged his disheveled wig and writing implements, then nervously waited as the room gained a volume of silent expectation.

After another full minute, William Pickering made entrance. His jowled face and sharp gaze loomed as he ascended with theatric deliberation and seated himself in the mayor’s chair. He too was draped in deep crimson, set apart from his lessers by a full measure of fox fur trim. The bulk of his lush robe puddled like spilled ink across the platform.

Pickering maintained his command of the room as he sighed heavily and set to work organizing the papers before him. His heavy ring tapped against a goblet as he perused the charge sheet. He then looked to the bailiff and nodded.

The bailiff again pounded his stave against the floor, pronouncing his words even as the echoes rang above him, “Bring forth the boy!”

The Sergeant at Arms, less stylishly dressed but sporting a tatty blue ribbon across his chest, grabbed Tom by the arm and pulled him from the dock, his iron chains falling all about him. He hardly knew where he was supposed to go, but the sergeant pushed him closer to the dais, so that he was forced to lift his eyes as up to heaven to speak to the mayor.

There was a gasp, barely audible, near the back of the room. Bess had slipped in quietly, heart hammering, and now clasped her apron in white-knuckled fists. Her face was pale, jaw clenched, eyes puddled with tears as she watched the child she had let slip from her grasp now cringing under the weight of the law. She dared not speak—to do so would only worsen his fate—but her eyes never left him.

This was all beyond Pickering’s notice, as his attention was drawn to the strands of dirty straw that fell away from the boy’s clothing and littered the floor. Tom annoyed him. Barely shoulder-high to the sergeant who yet held his arm, his shackles hung loose at his wrists, clinking faintly whenever he shifted—which he did over-much as children do.

To call him a Quaker would be to lend him dignity, as he was obviously nothing but an orphan taken in by these people. Yet he might be a currency and a means to tame the pamphleteers who were making Cambridge life difficult at the moment.

Pickering cleared his throat and asked with clipped voice. “Your name?”

“Thomas Lightfoot,” the boy offered.

“Your age?”

Tom hesitated, eyes darting toward James. “Ten. Or near it.”

One of the aldermen scoffed. “He looks younger.”

“He speaks older,” muttered the other.

The mayor eyed him with distrust, yet offered an opportunity to hang himself upon his words. “Thomas, do you know the difference between right and wrong?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Do you know what it means to sin?”

“Yes, sir.”

The mayor leaned back, satisfied, and pronounced for all to hear, “In God’s eyes, a child may be held to account when he understands sin and repentance. Some at seven. Some at twelve.” To Tom he said, “If you grasp the danger of your words, then you may be judged for them.”

Tom did not answer. A flush crept up his neck. James seemed about to offer an opinion but thought better of it. Behind them both, Vane caught the mayor’s eye and nodded approval.

Pickering then lifted the charge sheet for all to see and read aloud, letting each accusation fall like an anvil:

“Disturbance of the peace. Public blasphemy. Sedition. Disruption of university lecture. Defiance of lawful authority.” He peered at Tom over the parchment. “Do you deny you stood in the hall and said the Scriptures were not the Word of God?”

Tom lifted his chin. “I spoke the truth. I said that Christ is the Living Word, not the pages of Scripture.”

Pickering narrowed his eyes. “And in so saying, did deny the Holy Writ.”

“I did not mean so,” Tom said quickly. “I meant only—”

“Hold. Be silent.”

The mayor gestured to the clerk to record the statement. As that gentleman’s quill scurried across the page, he turned to the alderman on his left with a wink. “I have gotten ahead of myself. There is the oath yet to collect from him.” The two aldermen exchanged sly grins, then faced forward calmly as to await a satisfactory end of this portion of the proceeding. Vane lifted his chin expectantly.

Tom, meanwhile, startled at the word “oath,” and looked to James in his urgency. James met his eyes and prayed him courage.

Then, with a sigh of mock patience as he arranged the papers on his desk, Pickering turned back to the boy.

“You may take oath now and offer your repentance. Swear by Almighty God that you will speak truly in this court.”

Tom stood frozen.

“I may not swear,” he whispered.

Pickering’s voice grew louder. “You will swear, boy, or be held in contempt.”

“I cannot,” Tom said, firmer now. “Let thine yea be yea, and thine nay be nay.”

Vane could not remain silent. “You see, Mayor Pickering. Defiant even in childhood! The boy is a heretic and should hang!”

The aldermen leaned in for a brief discussion than none could quite make out. Pickering nodded grimly, then leaned forward with folded hands. “Thomas. You are young. The law under our Lord Protector shows mercy to youth.” At this he glanced at the doctor, who flinched. His relationship with Cromwell was not a strong one.

“If you now recant your words and ask pardon—not of me, but of Almighty God and His church—I shall remit your sentence. We can arrange at the Cambridge House of Correction to let you labor and learn a trade and repay the significant costs of this court proceeding. But no dungeon. No trial at the Assizes. No mark against your name.”

A wave of stillness swept the room. Even the quill of the court clerk paused.

Bess closed her eyes, lips pressed in silent prayer.

Tom swallowed. The courtroom, for a breath, seemed far away. He thought of the stink of the jail, the rats beneath his bed of straw, the damp that made his bones ache even after one night.

And then he looked up—not at Pickering, but at the crossbeam behind him, where a shaft of light had fallen on the worn carving of a lion’s head. He remembered the firelight in Whitehead’s eyes, the verse that rang louder than the whip: “For the Word of God is living, and active, and sharper than any two-edged sword…”

“I cannot take it back,” he said. His voice was thin, but unshaking. “It is true.”

Pickering sighed in a pretense of disappointment. But beneath the fatherly mask he thought, this might just make them squirm, these self-righteous air bags. Let George Fox himself come forth and beg mercy on the child.

“You were given a chance,” he said. “And you chose rebellion. So be it.”

He turned to the clerk. “Let the record show: the boy was offered clemency and refused. He is to be held until judgment may be passed at the Summer Assizes.” This last came with another glanced at Vane, who seemed to harbor a hope that the boy might yet hang by morning. Pickering added, as if offering the old man a concession, “He is to be remanded to the lower jail. The heretics’ cell. Let him learn repentance in the dark.”

At this last statement a murmur rumbled through the court. A student chuckled. “There’s a dungeon for Scripture-twisters.” Vane heard and while not completely satisfied, did not voice a complaint. He gathered his robes instead and left the spectacle, followed by the more respectable professors.

The mayor scribbled onto a paper and handed it to the bailiff. “Deliver this to the Keeper.”

The warder stepped forward, a burly man in frayed uniform, and seized Tom’s elbow. The boy glanced back just once.

Bess met his eyes. Her lips trembled, but she nodded. She would meet him at the jail.

They herded him to the holding room, and he was gone.

Vane’s ire was apparent. He was well-trained in keeping his temper appropriately, but within him boiled a desire for vengeance, and for the rightful punishment of this heretical child—the most dangerous sort—who might yet have a voice greater than any Fox or Whitehead within a few years. To his fellows he muttered in a voice that carried, “The boy should hang. Not so long ago, he would have burned!”

Amidst the tumultuous commentary that followed, the bailiff struck his stave hard against the floor.

“Silence! The court has given its judgment. Let none gainsay it.”

At this, students and townsfolk alike were cowed. He continued, his eye on the second prisoner.

“James Parnell, come forth for judgement.”

James rose with the clanging of chains and moved to the place where his young friend had just stood. His frame was slight and unbending, hair a bit askew without his hat, which had been knocked from his head and thrown back into his cell before journeying to the courthouse. His plain coat was dark with the dust of confinement, yet he remained placid. He had said nothing during Tom’s brief trial, and now all eyes turned to him, accusing him of whatever harm might befall the boy as a result of this folly.

Mayor William Pickering leaned forward. His gold chain of office lay heavy across his chest, the links catching the weak light.

“Master Parnell,” he said, with exaggerated patience, “the boy is your pupil. Your ward. You are older by far. The court sees in you a man who has led a child into blasphemy.”

He steepled his fingers and gave a sigh—half performance, half weariness.

“The child shall be held until the Assizes. Unless—”

He let the word hang, a note of false mercy.

“—you speak now. A public retraction. A declaration that he misunderstood your intent, that you do not hold the Scripture as lesser than the Son.”

James met his eye. Calmly. Without blinking.

“He spoke what was given him by God. I do not govern the Light within another.”

Pickering’s lips drew into a thin line. He stood, hands clasped behind his back, walking to the front of the bench.

“He is perhaps ten years old,” he said. “You would have him sleep in straw among cutpurses and plague-rats? You would risk his death, when one word from you might return him to the arms of that woman in the back who weeps for him?”

He gestured toward Bess, who now lifted her head, pale as the dead.

“Please,” she whispered. “James.”

Parnell’s throat worked once. His hands were bound in iron, but his shoulders were free, and he stood straighter than any man in the chamber.

“I will not buy peace with a lie.”

Pickering spat the next words like venom.

“Then you are no better than the boy. And just as mad.”

He turned to the clerk of the court.

“Remand the prisoner to the dungeon until the Summer Assizes—or until he begs for pardon, whichever comes first.”

A murmur rose from the hall, some shocked, some in hearty agreement, all standing as if to prepare for the next bit of business—the court of the mob. The bailiff stepped forward to receive the warrant.

James glanced behind him to see Bess being led away by a woman he realized was Eleanor Blakeling. He caught her husband’s eye and they exchanged a brief nod as the man quickly escorted his household out of a crowd already rising in energy—despite the malevolent force of the constables holding their truncheons at the ready.

The bailiff struck the floor with his staff—once, twice, thrice—and the hollow echo of finality rang out.

“Court adjourned!”

The Sergeant at Arms lifted James by his arm, steering him toward the holding room. Objects were soon flying at the both of them. At this the crowd let loose, so that two guards stepped over to carry him out of reach of the rioters’ hands toward the holding room. Tom watching from within beheld the rush of bodies even as the constables worked to push the most volatile out to the street.

The bailiff cried “Order! Order” and banged his staff to no avail. Tom’s heart sank with a dread certainty that he had lost the thread, and with it, lost his freedom.

The Shaming Ride

They passed quickly through the holding room to an outer door where a rough cart stood waiting, its planks splintered from years of haulage, with an ancient matting of straw still wet from the dung of hogs brought from farm to market that morning. Now midday, the air was sharp with the stench of the hay mixed into the tang of horse sweat and woodsmoke.

A murmur rose from the crowd pressing in against the courtyard gates. Joining the boys of the university—for the professors now stood with Vane as solemn as a murder of crows, a safe distance from the crowd but with a vantage point to witness the heretics safely delivered to prison—were mothers with baskets, tradesmen smelling of sweat and hot iron, boys with torn caps, all awaiting the promised spectacle. An old woman wailed for mercy, but a baker’s apprentice spat on the ground, wiping the spittle from his face with his apron.

Above the din, a sharp-voiced villager in a dark broadcloth cloak bellowed:

“Let them be paraded through the High Street! Let them taste the shame of their heresies!”

At this, a wave of excited cheers surged through the townsfolk.

The bailiff, his courtly sash exchanged for a brass badge and a sword in leather baldric, nodded once and pointed his stave down the cobbled street.

“So it shall be. Parade them.”

James, pale but steady, drew a breath as they were bundled up the wagon’s tailboard, their wrists yet ringed with the harsh iron cuffs. Tom tried to twist free, but a constable shoved him down onto the rough planks.

The wagon jolted into motion, the dun gelding stepping forward under the whip. Flies rose from the animal’s sweaty flank, swirling in the heat.

Around them, a chorus of cries began —

“Blasphemers!”

“Papist scum!”

“Spawn of the Devil!”

A few braver souls, hidden among the crowd, called gentler words —

“God keep ye!”

“Stand fast, lads!”

One woman, bonnet low over her eyes, tried to toss a roll of bread toward Tom, but it tumbled into the dust.

As the wagon rolled past the churchyard, the children running behind it pelted the transgressors and guards alike with dung. A constable swatted at them with a switch, cursing.

Tom regarded none of it, puzzling instead through the brief moments that had brought him to this place.

James moved close to him. “This attempt to shame us is but a blessing, young Tom, for it gives us a few more moments together. Now listen to me,” he urged, drawing the boy’s chin up to face him. “Ye must be strong. They cannot bind thine soul. Remember what George told us—the Light cannot be shut behind stone.”

Thomas wanted to believe it. He closed his eyes, letting James’s words anchor him.

“I fear I spoke too harshly,” Thomas confessed, shame boiling up through him. “I lost my wits, James. I let them twist my meaning.”

“Nay, friend,” came James’s reply, fierce as a bell, “thee spoke what was given thee to speak. No man can fault thee for that. The Lord sees thine heart.”

A silence fell between them, which only they heard beneath the bedlam all around.

Thomas asked, afraid to look James in the eye, “Will they hang me?”

“No,” James said at once. “They will threaten, they will scourge, they will call thee vile names—but they cannot kill what the Lord has raised up.”

Tom wiped tears from his face, though the action gave the mockers even more to crow about.

“Cry now, insolent gutter child! Cry thine eyes out!”

They had turned toward Castle Hill now, and such was the crowd that they continued following with impunity.

Tom looked at James, meeting his eyes. “They might keep me, though,” he choked. “For years, perhaps.”

“Then,” James answered gently, pointing to Tom’s chest, “thou shalt be a witness there as well. Whether free or bound, the Light goes with thee.”

The wagon stopped before the Gatekeeper’s House. Thresher waited on the steps, two guards beside him with pikes smartly raised, ready to welcome the prisoners’ return.

The bailiff stepped down from the front of the wagon and produced the warrant for the jailer. He received the paper and nodded as the bailiff bowed, then stepped back into the bowels of the gatehouse.

Meanwhile a constable was busy sweeping away the mockers, barking: “Make way! Make way for the prisoners!”

The guards dragged Tom and James down from the cart, their shackles clanging, and pushed them inside. There in the dim hall, Thresher held a lantern over the warrant and muttered, “Hand them to Duffy here.”

The constable looked and wondered for a moment if the old jailer was a bit loony, for he seemed to be alone. But the next moment there appeared out of the shadows a dangerous-looking turnkey, broken-nosed, his long arms thin but sinewed. He wore a dark leather coat with a dozen useful pockets, none of them ever empty. Under that a greasy leather jerkin and a ring of keys rattling like a miller’s chain

James looked up at him and Duffy grabbed his coat, pulling the boy near enough that he spat into his ear as he spoke. “You, little dainty one. Did you bring presents for your dear Duffy? I hear you stayed the night without paying.”

James spoke without fear, yet in a whisper for he knew all jailers lived by the pennies they cadged from prisoners and their families. “A farthing to buy fresh hay for the lad.”

At that moment Thresher turned back with his imposing presence. Duffy pushed both prisoners to their knees. James shot the boy a glance that held a thousand prayers in its silent force.

“Take the talker back to the cell with the door. Let me not hear his voice, Duffy, not even a prayer.”

“Yes m’lord. And t’other?”

“Heretic’s hole—bottom of the stairwell. Leave no torch—claims to have his own light. Let him pray all he wants.”

With that Thresher was gone and James was already in his cell, though Duffy yet stood imposing in front of the door with his hand out. James fished out the requisite farthing but seeing Tom’s expression he cried out, “Stand fast!” and received a kick in return.

Duffy locked the door angrily, pocketed the coin and growled, “you have just purchased your last word, mind. And cost your friend a bit of straw.” As turnkey came for him, Tom tried to draw his friend’s courage into his own heart. Duffy pointed toward a yawning archway that led to stairs.

A Heretic’s Cell

Duffy took hold of Tom’s shoulder with a giant hand that felt more of iron than flesh, as it steered him down a flight of stone steps slick with algae and rank with the sour stink of old damp. A rusty truncheon swung at the man’s belt, clattering against his ring of keys. With his other fist he clutched a torch that guttered and spat, throwing monstrous shadows across the walls. The passage twisted tight as a chimney flue, each step treacherously steep, so that Tom half-slid, half-stumbled his way down, the great iron shackles biting at his ankles with every awkward movement.

As they reached the final landing, the turnkey gave him a shove that nearly sent him sprawling in the direction of a cell no wider than a crypt, the floor scabbed over with mold, a single foul straw pallet crumpled in one corner. He climbed in obediently and the barred door slammed behind him. In another moment the torchlight vanished as Duffy silently climbed back out of the pit, leaving him with only the stink of damp stone and his own ragged breath.

Somewhere above, the heavy door clanged shut with a final, merciless report that echoed through the dark. To Tom it felt like a coffin lid sealing over his body.

The boy put his head in his hands, swallowing terror. But in the dark, a calm began to spread, thin but sure, a quiet knowledge that Truth was not so easily broken. He sat there for a long time, hugging his knees, every muscle trembling. They might kill him, he thought. They might do worse.

Whether free or bound, James had said, the Light goes with you.

That thought—impossibly small, impossibly strong—steadied him. He breathed in the sour cell air, but found he could sit up a little taller.

Above him, in his own a cramped cell, James prayed, travailing through the night for his friend’s young soul to stay fast, anchoring itself in Truth.

Outside, the night pressed on the old stones of Cambridge Prison, and a cold wind rattled the barred window. Somewhere far away, church bells rang the hour, indifferent to the fate of boys in chains. And in that silence, Thomas and James—no less than soldiers—whispered softly to God, their words weaving through the bars like a secret flame.