In his private office, the Mayor of Cambridge leaned over his cluttered desk, the wax seal of his latest warrant still cooling beside him. Across the room, High Sheriff Belton stood near the window, arms crossed, watching a pair of constables herd gawking townsfolk back from the courtyard. Behind him, half-hidden in the corner, was the considerable personage of Thresher, far too comfortable in a wide upholstered armchair. There was on his face a swath of crumbs and gravy from the meat pasty he’d brought with him, which he cleared with his hand and as quickly wiped off on the chair’s side. Pickering was glad he’d chosen leather over needlework.

The door creaked open. A black-clad figure entered without knocking.

“Dr. Vale,” Pickering muttered, casting a jaundiced eye his way. “I am unsurprised to see you.”

The Regius Professor did not sit. He moved to the center of the room with a proprietary sense that jarred its owner. The old man’s teeth ground together and he pressed his hand to his breast as if holding back fury. Looking first to the sheriff as if to assess whether he might be friend or foe, he finally pointed a gnarled finger at Pickering.

“I wanted the boy to hang and you let him live.”

The mayor shrugged and raised an eyebrow. “The boy lives…for now.”

Vale’s eyes narrowed. “I bear witness! I watched him slander sacred office. Before a hall packed with my very students and many respectable visitors, he accused us of heresy and greed. He all but bid us to throw away the holy writ, to burn it like useless chaff. That is not childish folly, it is blasphemy. You let him speak it unrepentant, and still you did not even whip him!”

The sheriff coughed slightly and spoke with an overly calm tone. “…And what then? Hang the skin from his ribs like washing?”

Thresher laughed and Vale turned with a start. Then he seemed relieved. “Jack Thresher, I was to visit you next.”

“Ah, to ask the same thing I suppose. He’s a child, Vale. A thin one. He wouldn’t have lasted three light lashes.”

Belton agreed. “You saw mayhem in the streets already. A public whipping would only stir more trouble. Especially as Parnell has raised Cain with his letters about the two women last year. We’d have these troublesome Quakers on every streetcorner shouting us down.”

“Yes,” said Pickering, “You don’t make the child a martyr, Vale. He’d haunt your university no end. Remember the bloodshed of St. Bartholomew and how it rankled over time.” he rapped the desk once with the seal stick. “There are subtler ways to extinguish a spark. If you want him broken, give it time.”

“Time!” Vale screeched. He wanted blood, not some gentle passing for this infested Quaker child.

“Yes, time. He’s young, stubborn, and doesn’t see he’s but a puppet for those seditious rebels. But dungeons make dull boys.” Pickering folded his hands. “The Summer Assizes is yet weeks away. He will break.”

Vale’s eyes yet gleamed with rage, but he held his tongue. Assizes. A higher court and a steadier mind to which he might appeal.

Belton grunted. “I’ll warrant neither one’ll last four days. And if by some miracle he survives, it’s a matter for a higher court. Your hands are washed of it.” He met the old man’s eye, reasoning with him on behalf of the city for which he was responsible. “The mayor is correct in this. No magistrate here wants the stain of sentencing a child. Leave it to the robed men at Summer Assizes to decide if he’s guilty enough to hang, or old enough to matter.”

Vale paced, his long robes trailing like a judge’s own. “And until then?”

Thresher gestured calmly. “No fears, Vale. He sits in the heretics’ hole. Shackled. Hungry. Listening to rats preach more sense than any he’s heard yet.”

“And what of Parnell? He’s older, cleverer,” Vale sneered. “More dangerous. He knows how to bide his time and well knows the benefit of his many admirers.”

Thresher rose, smiling. “I am happy to keep them both as my guests where none in the town dare come near. Let them rot in my tender care.”

There was a long silence.

Vale spoke again, low and bitter: “I say, that kind of rot doesn’t stay put. It spreads.” Belton’s mouth twitched. “My job is to keep the peace. Let their rot spread through stone if it can, but I won’t have it in my streets.”

Among Friends

February, 1656

George Whitehead stood at the window above a Norwich printer’s shop, looking beyond the clouds at the last vestiges of sunrise. All around him, the salty metallic scent of vinegared ink clung to the walls and rafters. There was a draft of fresh cold air by the casement and he breathed it in appreciatively. Fox, seated nearby, observed him and calmly ate of a large pasty newly provided by the printer’s wife.

She approached the young man with a serving plate. “Meat pie? It’s mostly potato and onion but I did put in a bit of potted lamb from the larder, as it is bitter cold out these nights.” George took one graciously, and though he could have eaten all of them, waved her off politely when she lifted the plate again.

“Tempt not to greed, Friend Naomi,” Fox smiled.

She ducked in a half-curtsey, out of sheer habit, then caught herself. “Pardon, Friends.” She seemed about to offer the plate again to Fox but thought better of herself and dipped another time with a nervous smile before retreating downstairs.

Whitehead ate as he crossed the room to the hearth, which radiated a goodly heat against the deep cold in the walls. He paused there, not wanting to irritate as his pacing so often seemed to do. Yet he was itching to keep moving. Pacing helped him think, and thinking was all he seemed to do now. Fox, having consumed his breakfast, turned again to pore over a stack of stained papers.

The younger man broke the silence. “Last Summer Assizes passed without a whisper, and now it’s nearly the Lent Assizes but no word. If they delay judgment again, we must force it into view. It seems obvious they do not want to risk trying James—not openly. He’s too eloquent by half. But Tom—”

Fox looked up. “They make an example of him.”

Whitehead didn’t respond right away. He leaned on the mantel and stared past the flames at the blackened brick, as if looking for prophecy in smoldering ash.

“Perhaps they don’t dare try him either,” he said finally. “Not properly. But they will not let him go. They’d rather let him rot than risk his words sounding in court.”

Fox rose and came to stand beside him. “He is not the first, nor will he be the last. You and I have both seen such sentences, and lived beyond them.

Whitehead turned, something kindling behind his tired eyes. “We could speak for ourselves. Now we must speak on his behalf.” He began pacing again, back toward the window. “We make the boy’s silence louder than their judgments. Let the whole countryside know he was never given a proper hearing. We flood the court with Friends. We put his name in every sermon, every pamphlet. Give them a dilemma; try him and risk a martyr or delay again and stand accused before God and country of imprisoning a child without charge.”

Fox looked at his lieutenant in ministry, not yet twenty, still a blazing fire for true faith. Yet also speaking from a guilt that distracted him from the overarching plan.

“We must remember all who suffer, men and women young and old, some pregnant or infirm. We have lost many lives while Tom has managed, with a family that supports him. And all of this, the losses we have suffered, we knew and expected. Most of us, in some way, have become martyrs to our past life.”

The young man sighed in frustration, desiring to throw something or break something or slam his fist even as he knew it was sin to do so. Instead, he spoke with what he hoped was a voice lacking in spite. “He is yet ill, and Bess as well, who can no longer come as often as she was. John Blakeling has no time to come at all, and his wife has not the stomach for it.”

Fox tapped his fingers upon the table with a mischievous glint in his eye. “Bess might have wed the man who could have done more good for the boy than any other.”

Whitehead laughed at this. “Yes, well, and what of her life once Tom is free? Hast thou met Friend Duffy?”

“No, I have not, but I have heard.”

The two chuckled, but a heavy air descended again as the younger man watched his mentor with a worried frown. Fox did not look up yet felt the stare. He pulled out a draft and held it out.

“George, I prepare now to appeal to the Protector himself.”

Whitehead received the page and carried it close to the window for perusal. It was an appeal to justice, couched in Scriptural precedent and signed by dozens of Suffolk and Norfolk Friends.

“We must be careful with tone,” Fox said. “If we demand too much, we’ll be branded rebels. If we sound too meek, they’ll ignore us.” “Then speak truth,” George said, “and pray he has ears to hear it.”

The Magistrate’s Docket

Cambridge Guildhall, June 1656

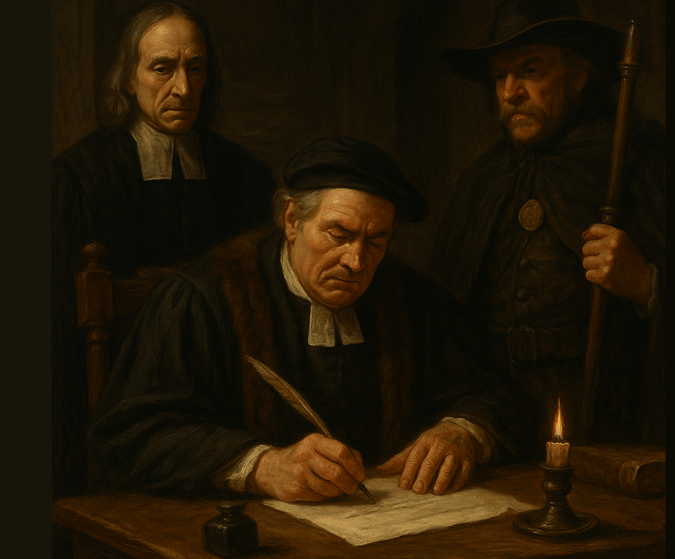

The magistrate’s private office was long and dim, its oak wainscoting stained near black with age. Though it was mid-morning, a single candle burned low in a brass holder atop the giant carved table before him. Clouds beyond the mullioned windows had smothered the day in damp gray. Rain ticked a ceaseless rhythm on the panes like a nail against a coffin lid.

Magistrate Edmund Arkwell, not yet sixty but with a face as tight and colorless as old parchment, sat hunched in a carved chair behind a sloping desk. His black robes pooled about him, and his signet ring left a faint grease-smudge wherever his hand paused on the docket.

He broke the seal on a fresh parchment with a silver blade—an unnecessary flourish, but one he enjoyed—and scanned the page.

“The heretic boy,” he muttered. “And the pamphleteer.”

At the hearth, Mayor Pickering stood with arms crossed, the glow of the fire outlining the slouch of his shoulders. The months had worn on him. His wig was limp with humidity, his eyes rimmed red from interrupted sleep and the toll of public unrest.

“They want a resolution before winter,” Pickering said. “There’s word George Whitehead is making visits—quietly, but steadily. London meetings. Petitions being passed about.”

Arkwell did not look up. “Let him stir his tea with prophecy. It won’t bring back public patience.” He tapped the parchment with a short fingernail. “The boy’s already served more than most for far worse. Two winters of bread and straw and still not so much as an apology from him.”

“Let him go,” Pickering said flatly.

Now Arkwell did look up, the chill of his gaze cutting through the room like a draught under the door. “You want a martyr, William? A child-prophet freed in a flurry of sympathy, then seen preaching in rags beside Saint Mary’s gates? No. Better to leave him where he is. Quietly forgotten.”

Pickering shifted his stance. “And the older one?”

Arkwell set the docket aside and leaned back. The chair groaned in protest.

“Too dangerous to try,” he said. “If Parnell so much as opens his mouth, the gallery will be on its feet before the clerk has named the charges. He’d win them over with that hollow-eyed righteousness of his. No sermon is so moving as one given by a dying man.”

Pickering’s jaw tensed. “So we do nothing.”

“We do something,” Arkwell said coolly. “We preserve order. We keep them off the docket. Neither of them will be called at Summer Assizes. It is within my discretion.”

Pickering turned slightly toward the rain-streaked window. “The Quakers will not stay quiet. You’ve seen their pamphlets. The boy’s name already stirs pity. Another winter in that cell and they’ll call him England’s Jeremiah.”

Arkwell smiled faintly, eyes not amused but triumphant. “Then we starve their hunger for outrage. No trial. No whipping. No scandal. Just silence. Eventually, even the righteous move on.”

The floor creaked behind them. The bailiff stepped forward, hat in hand.

“Shall I make note of the decision, my lord?” he asked, voice low.

Arkwell waved his fingers without turning. “Mark them both ‘continued without cause.’”

With a brief nod, he took up his staff and retreated with soft footfalls and the faint rustle of parchment.

Pickering exhaled and looked into the fire.

“And if they die?”

Arkwell, reaching for a quill, dipped it in the inkwell and began his next notation. His voice was almost kind.

“Then it was God’s judgment. Not ours.”

He blew gently on the ink and turned the page.

And so the decision passed in silence—no gavel, no bell—just a mark on paper, carried by a clerk who did not meet the jailer’s eye. By dusk, word had reached the Blakelings’ hearth, where two weeping women sat as John, his jaw set, read aloud the verdict that had not come.

Checkmate

The next afternoon, Fox and Whitehead worked together at a more discreet print shop, the last being shuttered indefinitely due to “unpaid taxes.” This one was in a farmer’s drying shed, with a rough table set beside a printing press still dusted with telltale bits of hay—evidence of its usual concealment. The tabletop was cluttered with parchment, quills, and a half-drunk mug of ale. Outside, the rain had not abated, and thick mud churned in the yard beyond the open door.

As the older man perused a newly printed pamphlet, young Whitehead watched the heavens with dissatisfaction. The elder asked, “Has there been no response for this page, The Grounds and Causes of our Sufferings? It is now four, five weeks since we let it fly.”

“None. It is as though the world’s ears and eyes and hearts are but closed to the inhumane acts against us. Perhaps I have merely informed the mob of new ways to cause bodily torment.”

Just then, a wiry old man approached, scrambling as quickly as he could across the soggy fields. His name was Simon Allen, a liveryman who brought fresh news with each return from Cambridge. This time he approached with his hat in hand, winded from travel.

He waited in the doorway while the two patiently allowed him to catch his breath, though both were nervous at the way Simon crushed his hat in his fists. “Friend Whitehead—”

George nodded, “It is good to see thee, Simon. I feared the coach had been delayed.”

The traveler joined them gratefully at the table, but spoke with lowered voice. “It was. I came partway by cart. One of the clerks at the Guildhall—Thomas Gray, a Friend in secret—he passed this to me before I left.”

He pulled a folded paper from his pocket and slid it across. The seal had been broken, then clumsily re-pressed.

George opened it, scanning. His eyes fixed on one line: ‘Cases of James Parnell and Thomas Lightfoot: continued without cause.’

He let out a slow breath. “They will not try them, neither one.”

Simon nodded. “Pickering won’t risk the crowd. And Arkwell won’t risk the boy.”

“Thus they choose nothing,” George said softly. “A prison with no sentence. The child forgotten.”

Simon hesitated. “They say one of the jailers asked how long the boy was to be kept, and Arkwell replied, ‘Until he’s no longer useful to the cause.’”

Whitehead closed his eyes. The words seared like embers.

“We all believe their fear his voice,” Simon added, “so they keep him silent.”

George rose slowly, folding the paper once, then again, as if to press his own resolve into it. “Then we must not be silent.”

He looked out toward the road, already knowing what he must do. “If they bury this in the dark, we will drag it into the light. Let them try to lock away a child’s words—we will put them in every pulpit, every printer’s press, every street corner between here and London.”

Simon blinked. “To London?” Fox spoke up. “To Cromwell. To Parliament. To any man who dares call himself just.” He placed a hand on Simon’s shoulder. “It begins with a child in a cell, but it ends in law.”