London, May 1661

A new spring had come, but winter’s cold remained. As if to spite the calendar, the fog off the Thames moved in with chilled malice, mocking both hearth and cloak. The heavy moist air carried with it the miasma of smoke and nearby waste mixed in with the river’s brackish breath.

London itself had been washed the day before by a hard rain. Puddles splashed along the flagstones at every passer-by, and the great hall leading to Parliament seemed a cavern of damp echoes.

The Lord Chancellor Edward Hyde, elevated after the King’s Coronation to Earl of Clarendon, walked slowly down the inner stone corridors of Westminster. The nation’s overly-zealous Christmastide—the first celebrated openly in 13 years—had added significantly to his corpulent form, now made larger with layers of velvet and ermine offset with heavy gold banded embellishments. He passed courtiers who breathed mist as though they were stabled horses; their gloved hands stretching toward braziers that hissed with the heat of wet wood.

The memory of November’s Privy Council clung like a bitterness in the depths of his stomach. Barbara Villier’s brazen intrusion—her perfume lingering where policy should have ruled. She had unsettled the meeting, and the King had half-smiled, as though mistresses and ministers alike were mere actors upon his own private stage.

As he neared the entry to the House of Lords, Clarendon—as Hyde was now called in public—prepared to endure a fresher torment: the scorn of young noblemen who wrapped their appetites in wit to suit their king, and who discoursed on the failings of the clergy not to heal them, but to purchase excuse for their own licentiousness. None stung more than George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham (relative of That Woman), whose wit had the cruelty of a rapier and the irresponsibility of a boy’s prank. The jesting of such men threatened to turn the nation’s wounds into sport.

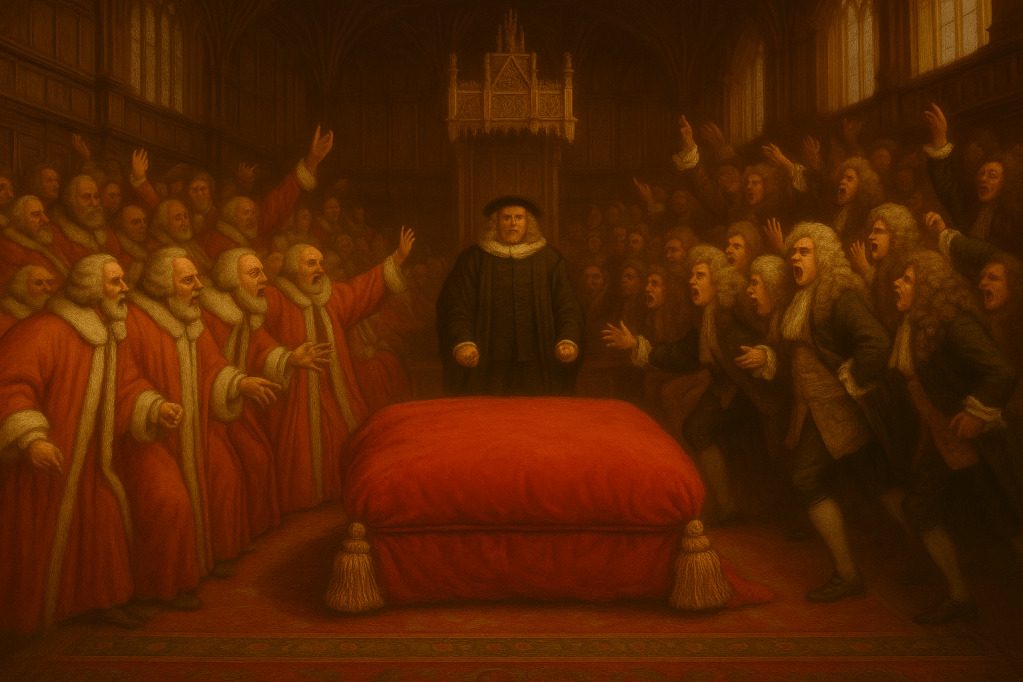

Putting aside these thoughts, Clarendon entered the chamber with resolve, the old gall congealing into something near iron as he walked solemnly past with the expectant eyes of both church and nobility. He carried with him the deliberation of a man who felt the burden of the nation upon his shoulders and feared it might bury him. The long train of his robe brushed the damp limestone as he went, with a step measured, almost judicial, as if each footfall were a ruling weighed against precedent.

As whispers and chuckles swelled about him, circling like invisible smoke rings from scores of unseen pipes, he thought of his early years as a lawyer and a member of Parliament—how he had once pricked at the pride of Charles’ father with the insolence of a rising country gentleman—though never with the snide jollity of these young upstarts. Yes, the decades had turned, and now he approached not a court of reason but a chamber bristling with fresh titles and tempers, each thorn sharper for being wrapped in velvet.

He wished the room had been grander, imagining a marble senate of antiquity with the sobriety it might have imposed. Instead, his steps echoed up toward weathered timbers, the sound muffled by faded Elizabethan tapestries—threadbare remnants of a grandeur long past. On either side, tall windows admitted a wan light that struggled against the guttering torches bracketed to the stone. The throne at the south end with its vast crimson canopy stood vacant now, the King having departed after the State Opening some days ago.

Clarendon approached the Woolsack, the seat of the Lord Chancellor. It was named for a great and costly measure of wool—that ancient staple of England’s wealth, dear enough to carry the kingdom upon its back. The giant cushion was covered with a crimson felt, offset by Tudor rose ribbons and tassels at each of the four corners. A few days previous, Avery had whispered an astonishing secret to him—that the ceremonial bale of wool placed there three centuries past had long ago been replaced with a packing of far more comfortable horsehair. He had appreciated the delicate decision, and that he was not the one forced to make it.

As was his wont, Clarendon did not yet sit but stooped to withdraw papers from his leather case, ordering them upon the cushion. He turned then and inclined his head toward the Judges’ Woolsack, where two senior judges who had been summoned by writ waited like carved sentinels. Their cushion, larger and plumped with horsehair rather than wool, marked a custom older than memory—an inheritance from the time when Parliament itself had been half-court, half-council. Once they had spoken freely in debate; now their voices were summoned only to settle points of law. Yet the Lords still deferred to them as to the keepers of precedent, the visible proof that every new statute stood atop a burial mound of forgotten ones. They returned Clarendon’s nod with the grave look of men ready to lend or withhold the weight of centuries.

Beyond the judges stretched a long table running half the length of the chamber, where the Clerk of the Parliaments sat with careful solemnity. About him clustered a bevy of clerks, clad in plain black surplices with stiff white collars, quills poised over inkpots. These were the finest of scribes, chosen not only for speed and clarity of hand but for their familiarity with the language of law, ready to render each new bill into precise script. When they had done, the Clerk himself would rise to read them aloud, and the Lords would debate, amend, and sometimes dismember the very words just written. On this table, bills lived or died, and some went on to alter kingdoms more lastingly than any seven-years war.

On either side of the chamber rose three tiers of benches draped in crimson velvet, the polish of the wood gleaming in the dim light of morning. To the Lord Chancellor’s right sat the Lords Spiritual in their long sleeves and short squared caps, favoring uniform over warmth. Closest, in primary position, was the aged William Juxon, Archbishop of Canterbury. He offered Clarendon a small, understanding smile—more in condolence than greeting. Clarendon gave a slight smile in return. Charles could hardly have chosen a safer churchman for the kingdom’s highest post: loyal in that he gave the prior king his last rites, yet at almost eighty he was too old and temperate to contest either the throne or the unsettled politics of the Restoration.

Beside Juxon, the Archbishop of York, also a man of kindly manner and quiet disposition. Next came the ever-watchful Bishop of London, flanked by Bishops Durham and Winchester, whom Clarendon thought more henchmen than shepherds. Lesser bishops clustered behind them on the upper tiers. If only they followed the temperance of their leaders! Instead, it was said openly in Cheapside and Westminster Yard that bishoprics were dangled like apples before ambitious men, that livings could be had for a promise of loyalty. No wonder the street preachers mocked them, crying that God’s vineyard was being let out to hirelings.

To his left loomed the Lords Temporal; earls in the forward benches, barons in the rear, and in between them the whole restless hierarchy of the peerage. Unlike the bishops’ watchful silence, the younger nobility shifted as though their robes itched; adjusting swords that had no place in debate, scribbling rude notes, and stifling their own laughter. The town had its own word for such men: rakes. Their affairs were no secret—mistresses paraded through the theatre, duels fought in the dark over debts or favors, fortunes spent on dice and silks while their tenants froze in the shires. All London knew, and all London talked.

Lord Clarendon coughed lightly, but it was the Bishop of London’s cold stare that at last won silence. Even so it was not a respectful quiet; it crackled, sharp-edged and expectant, the kind of stillness that hangs in the air a moment before laughter at a comedic performance.

Just one year ago, while negotiating for the King’s return, Clarendon had presented Charles’ Declaration of Breda which promised “liberty of conscience” to dissenting Protestants—a pledge the bishops had opposed with vehemence, and the young lords had ridiculed as weakness. He had stood his ground against them, speaking against corruption, urging sober discipline, defending the restored Church’s integrity. For his efforts he had been baited and mocked; pierced by Lord Buckingham’s barbs and Lord Ashley’s sly asides.

Yet Breda had been but words—an artful proclamation meant to soothe a weary kingdom. This day, the stakes were tangible. The House of Commons pressed for clarity on the rights and limits of dissenting Protestants, and the King demanded a resolution—an Act to end uncertainty. Meanwhile, the bishops, returned to their dioceses, maneuvered for influence and favor, intent on reasserting ecclesiastic authority. The Lords, caught between King and bishop, might not see how each weighty move marked their gains or losses. Would they rise to the task, or squander the day in jests and intrigue?

He began his speech formally, invoking the King’s pleasure and the solemn duty of those assembled. His voice was measured and deliberate, each syllable weighed as if to quell the levity that threatened. “Your Lordships, His Majesty has commanded that we address the disorders of these latter years: sects that reject law, worship, and allegiance to Crown and Church. It falls to this House to consider measures by which order may be preserved, and the peace of the kingdom upheld.”

The first ripple came from the temporal side. A mocking “Hear, hear!” sounded from the Duke of Buckingham, his voice bright with mischief. A few others echoed him, more to ridicule than agree. Clarendon pressed on, undeterred.

He spoke of the sects that multiplied like weeds—Quakers, Anabaptists, and most recently the violent Fifth Monarchists. Each claimed revelation, each undermined the parish order that had steadied the kingdom. Yes, all knew of the refusal of tithes, disruptions of worship, or even refusal to attend. Yet he could not but censure a Church given over to worldliness.

“We must not,” he said, “condemn a thinking people who call out nepotism, simony, ambition—these are cancers in the body ecclesiastical, and if unchecked, they only fuel dissent rather than quiet it.” He waited, shoulders squared beneath the weight of his robes, letting the chamber absorb the full measure of his words.

For a breath there was stillness, then Baron Ashley called across the aisle, “Better a bishop with nephews than a bishop with none!” Coarse laughter broke out as his neighbors nudged one another, grinning. Buckingham cupped his hands and cried, “Hear him plead for the Quakers!” Another barked “Boo!” as if he were at a pantomime. Ashley and his friends joined in as the booing quickly stretched into an ever-growing hum of disagreement. An elder baron called out, “Blame not the Church for the sins of the people!” At this, the clamor burst forth with a stamping of boots and sword-hilts.

With set jaw Clarendon adjusted his stance. He’d expected this—to their eyes, the plain-dressed Quakers were as unyielding as the Puritans had been in years past, and as such must be put down lest they gain civic power. He waited until the barons grew bored with their noisemaking, then continued with heavier emphasis.

“Your Lordships,” he said, “I am required to declare His Majesty’s intent: that peace and unity may at last take firm root in this kingdom. In exile, he pledged liberty to tender consciences, and I say to you, that promise remains his purpose still.”

A stir among the bishops signaled their unease. Clarendon’s gaze swept the chamber, meeting them squarely. “But liberty, my Lords, must never be mistaken for license. The King would have conscience preserved, yet not the commonwealth ungoverned. Promise must bend to necessity. To worship free is one thing; to forsake all order another.”

Now he pressed forward, his voice low and deliberate. “It is therefore not cruelty, but necessity, that compels the framing of laws for those who would have no priest, no oath, no army, no king. We speak of the Quakers in particular. These we must correct, not from hatred, but for the safety of all. And if some sharper remedies are urged,” he paused, letting his gaze rest upon the bishops, “know that such measures are not sought for the King’s pleasure, nor for mine. They are pressed only by the weight of counsel and the necessity of curbing disorder long suffered, lest the realm be further undone. His Majesty would have no man’s soul compelled, yet neither will he suffer this realm to be torn piecemeal by every new enthusiasm.”

He let the words settle, shaping the law as he believed it ought to be—as a check against sedition. This time the chamber did not laugh. A hush fell, like a cat who spies its prey and crouches with twitching tail. The temporal lords whispered among themselves, weighing how far such penalties might extend. Across from them, the bishops nodded gravely, pleased to see their former persecutors might now be persecuted with finality. Only a few faces showed unease—those who remembered the civil war and thought punishments a poor seed for peace.

From the first line of bishops a man rose with deliberate assurance, and the chamber swung toward him like a weathervane in a sudden gale. Clarendon closed his eyes, gritting his teeth. Gilbert Sheldon, Bishop of London, had chosen his moment. The Archbishop was frail, York too mild; the King had long taken comfort in such weakness, supposing it left him freedom to bend the Church to his will. But Clarendon knew better. Sheldon carried himself as though the archbishop’s throne already waited for him, and his voice, when it came, bore not only the tone of the Church but the settled authority of England itself. A chill ran through the Lord Chancellor’s arms—this was the man who would crown kings, not be ruled by them.

The bishop’s dark robes settled about him like a cloak of command and his neat fringe of bangs sharpened the intent in his eyes. In response to his rising Juxon slouched toward the throne side of the room with head turned away from his brethren, an elderly grimace fixed upon the floor. The younger lords smirked, restless as spectators at a bear-baiting. Unable to contain his amusement, Ashley whispered excitedly, “At last someone stands against His Majesty’s pompous schoolmaster!”

The air tightened; anticipation hummed like a drawn bow. When Sheldon spoke, his words landed with precision and force. “My Lord Chancellor—you have disparaged ‘sharper remedies.’ May we know what lesser remedies you have in mind? I have men beside me who might suggest we clap every Dissenter in irons for praying without priest or altar.”

He sat again with deliberate dignity, folding his hands as though closing a book; the motion carrying the weight of a sentence passed. A hush followed in his wake. Every man felt the weight of the gesture as if it were a command.

Clarendon raised his chin and, still standing, answered with the steadiness of a jurist. “These are stubborn folk; you will only create more martyrs than we already have. No more irons, my Lord of London; nor yet the lash. His Majesty desires not the multiplication of prisons, but the preservation of order, and no further punishments called down from pulpits. Let there be bonds for those first discovered in offence, fines for persistent disobedience, and, of course, penalties for unlawful assemblies—but measured, just, and applied according to law alone.”

The Bishop of Winchester snorted. “Fines cannot tame fanaticism, my Lord Chancellor. We have already seen these Quakers starve themselves before paying a penny.”

Murmurs swelled again, some agreeing, some shaking their heads. The mention of fanaticism struck a chord. The jeering subsided into uneasy mutters, for all remembered the bloodshed of the Fifth Monarchist uprising earlier in the year, and a light bond for sedition hardly seemed practicable. Yet even in that hush, Lord Buckingham’s voice rose light and mocking:

“So we are to coddle rebels lest they sulk, like spoiled children? A fine policy, my Lord Chancellor—perhaps next we shall ask these Dissenters what laws they would like.” Laughter burst forth again, though thinner, edged with unease. Before Clarendon could reply, Buckingham rose from his relaxed slouch and leaned forward, his smile sharp as a dagger.

“But let us say I agree on some points. Who then shall define an unlawful assembly? If three men meet for a drink and toast confusion to the bishops, shall they be shipped to the Indies? Or will you limit this law to the Quakers, since they lack swords to defend themselves?”

Clarendon let the laughter play itself out, then fixed Buckingham with a level gaze. “My Lord Duke, it is no jest to draw a line between loyalty and sedition. The law must distinguish the honest gathering from the factious conventicle. We do not speak of neighbors at table, nor of fellows conversing over a pint of ale, but of secret assemblies that renounce both Church and Crown, and by their very silence preach insubordination. His Majesty will not see the realm unstitched by such license. Yet neither does he command that we ship every scrivener or weaver to the Indies for his mutterings. The law must be sharp enough to cut disorder, not so wild a blade as to strike all alike.”

He let his words fall into the chamber like stones into a restless pond. Some bishops inclined their heads; others frowned. Among the temporal peers there were smirks and whispers as if the Chancellor’s moderation were mere timidity.

Buckingham shrugged, feigning innocence. “A fine line indeed, my Lord. One wonders how long it will hold.”

That was the signal volley. The younger lords erupted—raw, gleeful, and cruel. Voices rose in a chaotic chorus hurling suggestions like rotten fruit: “Get them when they meet under oak trees!”—a jab at the Baptists who once gathered to hear Bunyan.

“Mark those who won’t drink strong ale!”

“Ship ‘em to the Indies!”

Among the elders’ calls for “fines that bite” and “no quarter for seditious meetings” came the commanding voice of William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke ringing clear throughout the chamber: “Bring the Presbyterians to the Church of England’s table or strip their livings!” The suggestion hung in the air, met with a mixture of nods and murmurs.

Clarendon sensed the weight of the moment. In spite of the long history of such outbursts in the House of Lords, this must be the cruelest yet. He inhaled, ready to continue speaking the King’s peace. Yet before he could do so Bishop Sheldon rose again and the room’s attention bent toward him. When he spoke, his voice sliced through the chamber.

“Indeed, my Lord Pembroke speaks wisdom. We must insist upon fealty to the Church of England,” he declared. “Let Presbyterians and all sects born of recent years do penance and receive the sacrament in the proper house of God.” He let his echo fade, then fixed Clarendon with an unwavering gaze. “If we fail, no act of man or king can preserve the Church from contempt.”

Clarendon turned toward him patiently. Both men shared Episcopalian belief, but the bishop had the greater zeal for hierarchical order. “Your fervor is clear, my Lord of London,” he said, “but let the bill before us concern one sect for now—the Quakers. We will shape it for that purpose, that the Act may be both just and effective, rather than a general tool of suppression.”

A Senior Judge motioned for attention, his voice low and urgent. “My Lord Chancellor, might we confer a moment? There are matters I would clarify before the discussion continues.” Clarendon cast a measured glance toward Sheldon and stepped to the Judge’s Woolsack. By long custom the House expected its Chancellor to conclude his legal asides before business commenced. Yet Sheldon seized the opening and began drafting in earnest, his quill already scratching over his lap desk.

All eyes watched the Bishop of London, now in conference with his fellows regarding fines, bonds, and penalties for unlawful assemblies, speaking as though the Act were already his to frame. The bishops leaned forward with eager suggestions that would bind conscience to law, while the younger lords craned their necks like spectators at a sporting event.

They thrilled at this duel of words, far more entertaining than ponderous governance. A baron drawled from the upper bench, “And who, pray, shall spy out these unlawful gatherings? Will every parish constable now keep watch at barn doors? Perhaps a penny reward to the first informer who sniffs a Quaker down a lane?”

The jest drew scattered laughter. Sheldon glanced up and nodded to himself, making a marginal note. But Clarendon straightened from his conference with irritation, feeling indeed like a schoolmaster lumbered with an unruly class. His eyes narrowed as he saw the bishops gathering like a pack of crows around Sheldon. He raised a hand to redirect attention.

“We have already accounted for enforcement,” he said, voice calm but firm. “Let us focus on the measure itself: that no person shall gather in defiance of the King’s peace, and that penalties be justly applied.”

The chamber shifted, the talk bouncing back to fines and imprisonment. Buckingham leaned forward, a sly curl of a smile tugging at his lips. “Then what shall the penalty be for those gathering in defiance of the King?”

Clarendon gritted his teeth and exhaled slowly. “Moderate penalties, my Lords. Fines, a temporary stay in prison—no more. Let the law chastise, not devour.”

The word chastise unleashed another storm: some booing outright, others groaning theatrically. Several cried, “Shame!”

Sheldon rose deliberately with his draft, commanding the chamber’s attention. “Then let us draft it so: any person over sixteen found at an unlawful religious assembly shall be fined or imprisoned. This is not cruelty, my Lords—it is order. Without order, there is no peace.”

Ashley’s eyes gleamed. He leaned forward, smirking. “My Lord of London may well be the next Archbishop of Canterbury before Juxon’s last sermon is finished.”

Sheldon’s eyes flicked to him, a shadow of pride passing, then vanished beneath a mask of grave composure. “Let us first see this bill completed, Baron,” he said evenly, almost dismissive.

Ashley leaned back, quietly satisfied. “My apologies. How many shall form a conclave, then?”

A bishop leaned in with a figure—ten, another responding with twelve as if bidding him up at an auction—but Sheldon raised a hand, silencing them with the confidence of a man who had already decided.

He turned toward the clerks’ table, his words cutting through the chamber like a blade; precise, sharp, unyielding. “Write this: No meeting of more than five persons above the age of sixteen, gathered for worship outside the bounds of the parish church, shall be held lawful.”

A hush followed, brief and brittle, before the room seemed to breathe as one—and the breath carried anticipation, a desire for vengeance against others not like them. As the clerks scribbled, their quills unsure at first then scratching at pace with mechanical obedience, the eyes of the Lords and bishops met one another; nodding, smirking, whispering, feeding the current that had begun to surge. What had been a chamber of deliberation became a stage: the appetite for severity that had lain dormant now snapped into focus.

Clarendon sensed it immediately; his plea for measured justice suddenly drowned by the bloodthirsty tide. Suddenly it was as if the law had always been thus, and the crowd embraced the neat finality of the decision made. He felt his stomach tighten. Here was Bishop Sheldon, turning policy into an inquisition by headcount. It gave him a shudder to think what might happen if the man did indeed gain the ecclesiastical seat of power.

He sat heavily on the Woolsack, his presence swallowed by the momentum of the chamber. Here, at last, the will of the King, the temperance of the Chancellor, and the slow prudence of custom had been overtaken by a raw, electric thrill of domination and the taste of punishment—the same instinct that drove mobs to the scaffold. Clarendon’s stomach knotted; he knew, with a cold certainty, that once such a current began, no careful word would stem it.