Late July, 1656

The coals in the hearth had sunk to a sullen red, giving off just enough heat to justify the fire but not enough to drive out the creeping damp that clung to the old plaster walls in this, the coldest July of memory. The heavy curtains were drawn tight, muffling the hum of the street and throwing the room into a kind of permanent twilight, lit by a single lantern on the table.

Pickering leaned back in his chair, boots stretched toward the fire. With his thumb tucked in his belt and wig on the desk beside a battered pewter cup, he looked more miller than magistrate, but the glint in his eye made clear he knew his power.

Vane stood across from him, his hard-set jaw jutting out over a spotless collar offset by inky black robes. His eyes burned with scorn as he clutched a recent pamphlet.

Between the two, pacing slowly as though considering a problem of cattle or taxes, High Sheriff Belton was uncharacteristically lost in thought. His traveling cloak still about him, the brass clasp at his shoulder yet flecked with road dust. His gloved hand held a long riding crop that tapped softly against his leg.

“I do not care,” Vane said, low and seething, “if the Lord Protector himself has grown sentimental. The child is no innocent. He should have been whipped. Twice.”

Belton waved his hand. “We’ve already agreed we’d have a martyr before the judge sits and every hedge-preacher crying out on it from here to Yorkshire.”

Vane’s mouth twisted. “So instead you put him as a debtor in the county House of Correction? What lesson does he learn there? How to count nails and sweep floors?”

Thresher, once again eating his lunch in the comfort of the mayor’s best chair, held up a hand. “It ain’t the parish poorhouse he run from afore. He’ll be under Vexler.” The others looked at him as he nodded. “More prisoner than debtor, if you get my meaning.” His growl gave the words weight, settling like ash on the table.

Vane arched a brow. “I know of Vexler. He will work the boy, but to no good end. The child will die of starvation within a year.”

“Aye,” the jailer said. “Still a debtor’s sentence if ye like, but there’s no kindly warden with bread and milk. He keeps a mastiff ever ready to chase down the runaways and a smith who enjoys his duties too well. Let the boy try to break free again.” He chuckled as crumbs poured from his mouth.

Pickering nodded. “Clever. No lash, just discipline. And if he bites a turnkey, well—boys get bruises. No judge in London will cry foul.”

“Still,” Vane said, pacing now himself, “I’m not content. What of Parnell who made him dangerous? Trained him like a parrot, filled his head with all that insolent fire.”

“Parnell will be heard at the Summer Assize,” said the sheriff. “This is what concerns me. I’ve the peace of Cambridge to consider.”

“He’ll speak at the Assize,” Vane snapped. “And win hearts with that sallow face and saintly stare. He needs to be compromised, not martyred.”

Pickering leaned forward, fingers steepled. “His release is already ordered, but—he cannot go unless the fees are paid.”

“Fees,” Vane repeated.

Thresher smirked. “He’s earned a weight of debt, as he’s insisted on paying every charge for both him and the child. Seven shillings each month for straw, two more for the turnkey. Bread, water, lamp oil, cleaning. All doubled for two prisoners. I reckon he owes us…well over thirty pound now.”

Vane’s eyes glinted. “Ah, it would take the better part of two years’ labor to pay it. I am pleased. Let him taste the hypocrisy of his own gospel. Bound not by steel—but by coin.”

“If his Friends pay it?” Pickering asked.

Thresher shook his head, laughing. “He won’t let them. On principle.”

A moment passed as they all pondered this nonsense.

Then Pickering added, “I’ve had another thought as well.”

Vane looked up, waiting.

The mayor held a finger in the air as if conducting the last note of an orchestral piece. “Shift him to Colchester.”

“Ah,” smiled the sheriff. “He has ties there—bad ones to spite the Friends and sympathizers. Let the Essex men carry this trouble for a while. Their magistrates may prove…less susceptible to petitions and tears.”

“A shift of jurisdiction?” Vane mused, “Is that allowed?”

Pickering shrugged. “We have precedent. The original offense can be said to have straddled the shire lines. I can write the brief myself.”

The sheriff tapped his crop once against the floor. “Colchester Castle. Strong walls, harder men. They’re less likely to let his kind play martyr.”

Thresher shook his head wonderingly. “Aye, they’re cruel at Colchester. The boy will see what he’s missed when he compares our kindness to theirs.”

“And if he dies?” Vane asked quietly.

“Then we sigh,” said Pickering, “and point to his refusal to recant or pay his debt. All legal. All clean.”

The men were quiet for a moment, each calculating.

Then Vane spoke again, quiet and precise. “The record must show the child was offered leniency. That he refused it. That his continued suffering is not of the court’s doing, but his own.”

Pickering nodded. “Already written.”

The sheriff adjusted his gloves. “And Parnell will be watched betimes. Thresher, if he so much as utters a sermon to the chimney soot, send him to the pit, gagged.”

Vane nodded, “And when Parnell fails after too many days without light or meat, I will tell my scholars he should have repented. They will agree, no doubt.”

Pickering refilled his cup. “The world prefers its rebels dead. Much less trouble than when they talk.”

Two soft taps sounded at the thick wooden door. A clerk entered and bowed, handing the mayor a scroll with a meaningful look, then disappearing again like a shadow.

Pickering looked up with a slow smile. “A runner from London. Cromwell’s seal.”

Vane snorted. “Does it say we are to kiss the boy’s hand and crown him king of the Quakers?”

Pickering cracked the seal and unfolded the letter. He read, eyebrows arching, lips pressing together. Then: “No, only what we already heard. The boy must be moved and Parnell heard in court.”

The sheriff scoffed. “And yet we’re decided. Neither will walk free.” Vane turned back to the fire. “Good. Then let them learn what the mercy of England looks like.”

Colchester

Late August, 1656

The Medieval meeting house was not built for justice—nor for vengeance—but this morning, it had been summoned to serve both. A bitter light filtered through the mullioned windows, each pane warped and pocked with air bubbles that turned the world outside into a dream of icy mist and pale rooftops. The cold that haunted the countryside all summer had turned cruel in the night, so that the air inside the hall was sharper than the wind outdoors, and still as a crypt, as though the great timber frame held its own breath.

Slowly the servants arrived who would kit out the room for a trial long awaited. A grim-faced woman in woolen apron entered from the back, summoning after her a boy about Tom’s age and a little girl of perhaps five, both with cheeks red from cold. She pointed out each of the fireplaces in the room and motioned toward the woodbox nearby.

As they padded away she looked above her, to rafters that met in a humble crown, uncarved and soot-darkened, their unadorned ends simply pegged. The ceiling sagged slightly with age, heavy beams listing like the ribs of a grounded ship. No crest or coat of arms broke the lines—merely wood darkened by the smoke of generations. The only color came from faded limewash, now chalky and flaking near the corners.

She crossed herself and looked for the boy, who was already returning with the stiff bundle of twigs that served as her broom. In his other arm he held several small logs, and the girl beside him hugged a bundle of kindling to her chest like a doll. The woman pointed them on to the first fireplace, then began to slowly sweep the wide-planked floor, not looking up even when the great silence was broken by lumbering men who dragged the benches into rows behind her, the bang of wood on wood echoing like distant cannon fire.

No bench was evenly made. The better ones for the gentry had arms worn shiny by years of elbows. Lesser, rougher benches bore gouges where the bored had once carved their names. Beyond them the boy had crouched by the first hearth at the south wall, coaxing a reluctant flame to life, his breath visible as he blew carefully into the dry curls of birch bark. The girl did not speak, only waited for instruction. When he nodded, she passed him one stick at a time with priest-like reverence. When the kindling took hold, they fetched more wood and moved on to the next, to start, to feed, to tend every fire by turn until the woman came to check each one, hauling bigger logs to add until the flames grew high.

As the hour wore on, the quiet was interrupted when the Colchester bailiff entered and surveyed the room. He was a broad man with a nose like a squashed pear. His mulberry doublet was tight upon him and he tugged it every so often as he directed the porters and guards.

Now they prepared the room for battle. This was to be no tedious roll-call of drunks and petty thieves. At the far end of the hall, they set a cage-like structure to stand as the prisoner’s dock. A smaller bench faced it, meant for witnesses. And beside that, a high stool and rough-hewn table where the judge would sit, a thin rug thrown across the top to disguise the fact that the legs were mismatched. A clerk’s satchel already waited on a smaller table nearby, along with a sealed parchment and jar of ink gone half-frozen in the night.

A carpenter entered and began hammering together a railing to separate the jurors’ space. The sound rang out with disapproval. The town’s elders had debated whether this trial should even be held here. But with no dedicated courthouse, this plain facility generally used for sermons and civic quarrels had been judged sufficient. Even preferable, they joked, for a Quaker’s taste.

In time, the children finished clearing the wood detritus from around each hearth and prepared to leave with their mother. She paused and again looked to the heavens. “May God forgive them,” she muttered, not specifying whom.

At that moment, a gust of wind rattled the panes, and the little girl flinched.

“‘Tis only the day beginning,” her brother said gently, and held her hand as they padded away.

First one then another of the workers noticed a new sound, as did the bailiff. Beneath the scrape of benches and crackle of flame, they could hear it: the boots of men approaching from the street, and the creak of the castle gates swinging wide. The prisoner was being transferred to a makeshift holding room.

The trial of James Parnell had gained the infamy of whispers from city to city, and while the transfer of the prisoner was accomplished in the silence of the night, beams of foreknowledge had cast upon this secrecy a light of suspicion. Even the Quaker-haters had wondered at the necessity of a quiet transfer. They lined up outside for their turn to gawk.

As many as could waited under the eaves, wrapped in cloaks and whispering, each group wary of the others. Most were tradesmen and housewives, their curiosity draped in righteousness. Others stood back with arms folded, lips drawn tight—those who had read the boy’s pamphlets, or heard his voice echoing in the streets months ago. What kind of young man speaks so boldly of judgment? Of a kingdom not made with hands?

The transfer was accomplished all too swiftly, so the crowd was left to wait for entry. A pie-seller with red face and a soot-smeared bonnet brought round a basket of small mutton pasties. Across the way, a barrel of boiled apples steamed gently, filling the air with a sweet, earthy perfume that mingled with the sharp tang of roasting chestnuts from a brazier nearby. A boy cried the wares at his family’s stall, “Mulled cider! Still hot! Warm ye hands while waiting!”

No market day was ever quite like this—there was no laughter, no fiddler on the corner. Only the scrape of boots, the hush of gossip, and the slow press of bodies jostling toward the door, drawn by the promise of judgment.

Within the towering walls the odor of shoe leather and unwashed linen mixed with the heavy smells of tallow and parchment as the souls upon the street made their way inside. Most were clad in trade or poor man’s clothes. Those among the gentry entered by a separate door and were escorted to their places. Clergy and college alike were sparsely represented, but spies for both attentively stood near the door, ready to run with word of the outcome. Quakers—their hats firmly in place—were few as well, for many had already been imprisoned. The community at large thought best to send only Whitehead and two others, the rest to wait at home for news.

Constables stationed about the room kept a wary eye, truncheons close to hand. The tension upon them as they scanned the growing crowd was palpable. At last they signaled that the room was full, both seating and standing. Calls of disapproval rang from the street as the great doors closed with finality.

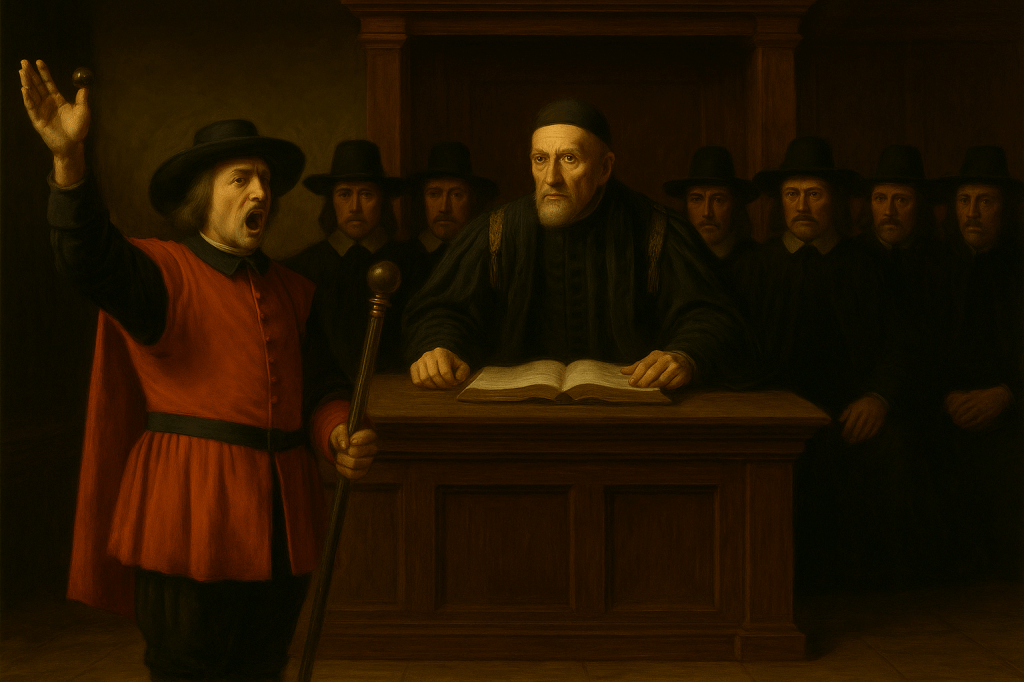

A hush struggled to settle as the Colchester bailiff entered, having donned a flowing tabard with the county crest worked crudely upon the right chest. He was now equipped with a staff of office capped in shining brass, and he rapped the butt of it hard upon the boards, enough to make the floor tremble, and the uneasy crowd shifted.

His gritty voice bellowed: “Oyez! Oyez! Oyez! This Honorable Court of Assizes now sits in judgment under His Highness the Lord Protector. Let all keep silence and give heed!”

A whiff of pipe smoke and sweat drifted through the air as the bailiff ceremoniously removed his hat from atop his wig and placed it upon a stool beside him. George and his fellows did not move, while all others made much of removing their hats according to tradition. Disgruntled murmurs rose again but the bailiff raised his voice again, cutting across the growing discontent:

“Let none disturb the peace whilst the magistrates do sit!”

All voices hushed. He stepped back, folding thick hands atop his staff, waiting as the justices of the peace entered and filed to their seats in solemn procession, their robes an ominous sweep of black wool. Whitehead glanced up to see them, dismayed at his own curiosity. Their garments were stiff with braid and edged in somber bands of scarlet. The cloth, heavy as a funeral pall, fell in thick pleats over broad shoulders, broken only by crisp white collars that framed their severe faces. Each wore a flat-crowned hat, the brims dipped low to shade watchful eyes, as cold as a winter fen.

The bailiff sounded again, his staff echoing in the rafters. “All rise!”

He turned to the door behind him and stood to attention as the judge, Sir Eldon Swithin, walked directly to the bench without fanfare. He was skeletal, his face narrow and long with cheeks like folded parchment and eyes so pale they seemed nearly blind. But they missed nothing. His mouth, nearly lipless, twitched as though it were constantly tasting something bitter. He moved with quiet efficiency, taking the bench like a spider calmly ascending its web.

The bailiff cried out, “All be seated. Let the jury be seated.”

The crowd sank back. The jury, already selected that morning from among the middling sort of Colchester—innkeepers, glovers, coopers, and tradesmen loyal to the Protectorate—were seated and stone-faced, though one or two kept darting glances toward the prisoner’s dock.

Swithin nodded to the Sergeant at Arms, who stepped back to the holding room for the prisoner. He returned half-carrying James Parnell, his frame sunken beneath the weight of weeks in chains, his skin pale as a snow drift. The Friends who had seen him before his imprisonment gasped, but then two or three closed their eyes and prayed. The others of their number beheld their brother sorrowfully and moved their lips silently in an invocation to God on high.

The prisoner fell unceremoniously into the dock, then pulled himself up to lean as best he could against the rails. The judges shifted and sniffed as though offended by his stench of his filth and illness. Their mouths, narrow as knife slits, betrayed no hint of warmth nor concern, only a well-fed certainty in their own rightness, as if the law itself had taken human shape in their bodies.

A murmur was building through the great hall.

“Silence,” the judge said calmly. He had not raised his voice, nor did he need to. He had the kind of voice that, though unhurried, could slice a man in half.

A clerk in sandy parchment-colored robes stepped forth to read the charges:

“James Parnell, you stand accused of disturbing the peace, refusing the authority of the Church, defaming lawful magistrates, and publishing seditious writings contrary to the order of England and the well-being of its people.”

James, for his part, felt the chill settle on his bones as he waited for earthly judgement, ankles and wrists calloused from his chains. His lionish bearing had all but disintegrated under the weight of cold, illness, and starvation.

“You there,” Swithin nodded toward James, expectantly.

James looked up slowly, aware of the blazing eyes of the bailiff upon him. He met the judge’s glare.

“You are accused of sedition, and of publishing seditious libels against the officers of this borough. How plead you?”

“I deny no word I have written. But I am no traitor. I speak only what God has taught me.”

Sir Eldon regarded him for a long moment.

“God has taught you to insult His ministers?”

“God has taught me to name what is false,” Parnell replied weakly, the effort leaving him out of breath.

The judge looked at the jury as though sharing a private joke. “Ah. So the boy would have us believe that his insolence is righteousness, and our laws are lies.”

The bailiff snorted and many in the crowd joined in. One of the constables near the back nodded approvingly.

Swithin leaned forward. “Let the record state that the accused does not deny authorship of the pamphlet named, A Shield of the Truth, nor does he recant the blasphemies therein.”

The clerk scribbled rapidly.

There was a pause.

Then a rustle of parchment as the prosecution produced the offending text—bound in cheap cover, already thumbed and stained. A pompous, balding solicitor read aloud a passage in which the clergy were described as “men who sell the gospel for coin and preach to itching ears.”

Swithin’s voice was sharp: “Do you deny this statement, Master Parnell?”

James raised his head. “No. But it was not written in anger. It was written in sorrow.”

The judge let out a dry, scornful breath. “And yet it reeks of rebellion. You style yourself a prophet, a scourge of Babylon, a child Jeremiah. But I see a boy who would upend the realm with a pen.”

There was laughter among the gentry. Whitehead made as if to stand, but a constable barked at him to sit.

Sir Swithin gestured slightly, and the prosecutor stepped back. “You may not be hanged,” he said to James, “for you are yet young. But youth is no excuse for poison.” Having done with the prisoner, he waved him off and turned to the jury.

“You’ve heard all that will be said. Do you have a verdict, or do you require more evidence, or…” he sniffed disapprovingly, “have you some need to deliberate more?”

The carefully chosen men leaned in together for a brief whispered conference, then sat back, straightening themselves. The foreman announced, “We have no need of further deliberation.”

The crowd seemed transfixed, some whispering to a neighbor, others craning to watch as the foreman, following court protocol, motioned toward the court clerk. This young man rushed from his desk to the jury box for a quiet word and as quickly returned to write the verdict. He then delivered it in more composed manner to the judge.

Swithin read, raised his eyebrows only slightly, then gestured to the bailiff. That worthy then interrupted the quiet with a loud bang of his staff upon the floor, crying, “Let the prisoner rise for the verdict!”

The prisoner was still clinging to the dock rail but lifted his head without fear.

Swithin looked at him almost casually. “James Parnell, on the charge of publishing seditious writing, you are not guilty.” He then paused and lifted a paper from his desk, “However, there is a matter of debts from Cambridge jail in the amount of forty pounds.”

A gasp splayed itself across the room—near two year’s wages for a working man, and it seemed obvious Parnell was not capable of lifting a finger toward any type of employment.

The judge lifted his voice over the hum of the crowd. “You shall be returned to Colchester Castle, as you remain in my district. There you will stay until the debts of your confinement are satisfied.” He then looked coldly at the Friends. “Let none mistake this for clemency. Your gospel does not release you from the law. Nor from the cost of bread.”

Whitehead stood and offered, “We stand ready to pay this debt, or shall do in short time.”

“No.” James’ voice rang clear to the rafters. He did not look away from the judge. “I am committed to be kept a prisoner, for I am the Lord’s free-man. There is no price to be paid.”

One of the farmers crowed, “He’s a loon, this one!”

But before anyone else could answer the bailiff bellowed the court to adjournment and the constables were already ushering the standing crowd toward the door. The spies among them clawed their way out while the remainder shuffled along, whispering in wonderment and with opinions of every kind.

For his own part, Judge Swithin handed his documents to the court clerk and muttered, “If the boy lives out the season, I shall be astonished. And if he dies, let it not be said that I shortened his days.” Then he rose, pulling his cloak around him as a raven folds his wings, and departed.