October, 1656

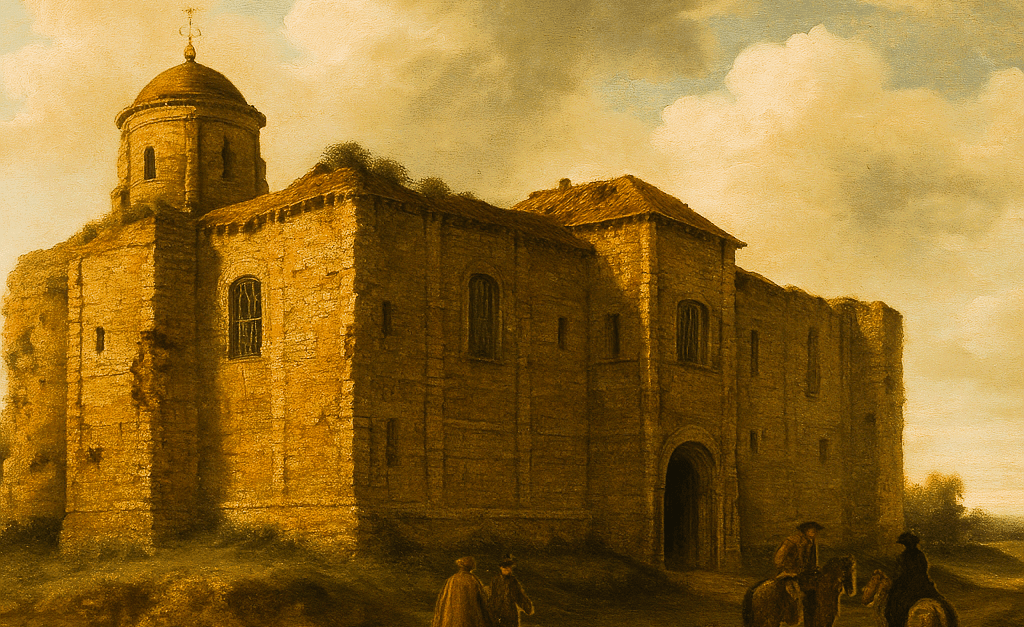

The north wind had turned cruel. It rose off the sea and swept through the streets of Colchester like a huntsman with a lash, driving even the dogs to seek corners of shelter. Under the sullen sky, the old Norman keep rose like a sooty fist against the sullen sky, its weatherworn stones pocked and slick with rain. Once a bastion against Viking raids, now it housed petty thieves, dissenters, and a youth who would bend his neck to neither bishop nor magistrate.

George Whitehead hunched his shoulders beneath a rough gray cloak as he stepped over the threshold, nodding back to his companion and fellow member of the Valiant Sixty, Richard Clayton. The latter looked far older than his twenty-seven years, his beard being stiff with frost where breath had clung and frozen. He took a grateful breath near the heat of a brazier flame and stopped. The men then glanced at each other, brushing their noses. It was not just the age and mildew of the dungeon—that was a well-known experience for both—but something faintly sour, like old vinegar left too long uncorked.

They gave their names at the inner gate. “We were told to come here at noontime to visit our friend.”

A shadow crossed the turnkey’s face, on which he kept a look of disdain, but with his hand he motioned for them to follow. He stopped before a guard at the inner gate and as if he’d forgotten something, motioned for Richard to present the coarse sack strapped across his back. It was filled with bedding hand-stitched in quiet defiance by the women of the Meeting near Woodbridge—blankets, woolen hose, and a hard parcel at the bottom.

“The Quaker prophet and his nursemaid,” he muttered to the guard. To George he proclaimed, “If you’ve any meat in there, best keep it hid. The rats take tithe before the prisoners can get it to their mouths.”

They passed to the inner bailey, following the still-scowling jailer. Two voices sounded in the hallway, the warden and his wife. At this the jailer quickly opened another door that led to the lower cells. Only when it was locked behind him did his face rest into exhaustion.

George slipped a coin into his hand. “This is for you, Friend. I know thou hast said thou wouldst not take a bribe, but take this gift from all of us who are ever grateful.

The turnkey took the offering and nodded, whispering, “I cannot say how long thou may visit, but it must be quick. Them two, they are devils. Thine friend is well-mistreated here. The other jailers lay odds on whether he’ll make it to All Saints.”

He listened for the couple to pass before leading them to the lower cells. Their boots echoed off the uneven stone floor, softened only by patches of straw and centuries of footfall. From above, a dull light filtered down through murder holes and slit windows. The smell was worse than any they’d found in the jails at Bury or Norwich—a stew of sweat, mildew, cold ash, sewage, and rot. Here and there, a prisoner muttered through cracked lips. None looked up. On either side, stones retained centuries of winter, and now water from the long rains dripped methodically down, building thick drops of ice that clung to the walls.

At a landing, the turnkey set the lantern on a hook and gestured toward a heavy oak door reinforced with iron straps. “He’s down here.” He threw a bolt with a grunt, and the door creaked open.

“Mind your feet.” They stepped down into a chamber whose vaulted ceiling arched into darkness. In the center, a square opening yawned in the floor like a wound. A rope hung from a rusting pulley. Around the hole were bits of rotten vegetables, moldy crusts, and rat droppings.

“Come along,” he coaxed. “You’ll not have much time.”

“Where is he,” Clayton asked, looking into the shadowed corners.

“He ain’t in a proper cell, mind—he’s in what they call the ‘Gospel Room.’ Not meant for living. Or dying, for that matter.” The two continued to look around them until the jailer turned George forcefully as if he were a dull scholar. “Down there,” he pointed, swinging a rusty lantern. The flame sputtered and cast nervous shadows across the tunnel walls.

“Why is he placed there?” Whitehead asked.

The turnkey spat without breaking stride. “As they say it, because he speaks too fine for a rat cell, but not fine enough to dine with judges. That’s their Essex justice. He’s lucky not to be in the oubliette.” He stood waiting for one of them to make a move.

“You mean—?” Clayton began.

The turnkey nodded. “There’s no stair, Friend. If you want to visit, the rope is here. I’ll make sure they don’t come in, but thou hast only a short time.” He turned and left them to it.

Clayton crouched down and tested the rope, frowning. Then, with care, he lowered the sack. It disappeared into the gloom below, swaying slightly until it struck stone.

He listened, then stepped back with disappointment. “He makes no sound. I must go down.”

Whitehead stayed him. “I’ve less weight than you, Friend. Let me try the rope. We can send someone with a better rope later, now we know the need.”

He knelt down and gathered the rope in both hands. It was damp, the fibers swollen and cold. He lowered himself slowly, his boots searching the curve of the shaft until at last they scraped against stone.

The cell was barely a room—more a hole with three sides of unmortared wall and a fourth of the castle’s living rock. A faint mold glowed faintly green in the crevices, like bruised skin. In one corner, on a pile of rotting hay, was James Parnell.

He stirred as his visitor gathered up the bag and approached. His face was still pale, though more from lack of light than illness. His eyes, though sunken when they met Whitehead’s, were still alight.

“George,” he whispered, and allowed himself to be drawn into a gentle embrace.

“Friend Richard has also come. We bring warmth. And words.”

James sat up with effort, drawing the woolen bundle close as though it contained light itself.

“I dreamed of thee last night,” he said. “And of that great room in Suffolk where they read my letter aloud. Was that a true thing, or a dream?”

“It was true,” said Whitehead. “The Friends took comfort from it. So did I.” He looked around. “Do they bring food each day?”

“Not always. A crust, a cup. But not each day. And I must climb—”

He glanced toward the rope.

Whitehead’s jaw tightened. “They make thee climb for thy sustenance?”

“If I do not, it is lost to the rats.”

George looked at the concrete paving. “And if thou fall?”

James smiled faintly. “Then they say I chose death by pride. But Friend George, you must know that all is in God’s hands. ‘I have food to eat that ye know not of.’ And also water that pours clean through a crack over there.”

A silence followed. Above them, Clayton called softly down, asking if all was well.

Whitehead replied, “As well as may be, in this place.”

Clayton’s voice trembled slightly. “Tell him my wife sends these with her tears and her prayers.”

James clutched the blanket tighter, breathing in its scent. “It smells of rosemary,” he murmured. “And baking.”

“Come,” said Whitehead, emptying the bag to take it up again. “I’ll help thee. See the sun, even if it is weak.”

Together they made the slow ascent, James clinging to the rope while Whitehead bore as much of his weight as he could from below.

Clayton reached out with both arms and hauled the boy to the stone. He laid him gently down, then offered a sliver of the apple cake and a cup of weak beer.

James sipped, then looked at them both with a new light in his face.

“I feared I had been forgot.”

Clayton inclined his head with grave affection. “We bring the greetings of Friends in Suffolk and Norwich. Many pray for thee nightly. We do not forget you.”

“Never,” said Whitehead, and his voice cracked. “This warden means to keep us from you, and forbids all visitors. Praise God there is one here who is a Friend, but you must not acknowledge him lest others hear. With his assistance, we will try to come again soon.”

James smiled with a little too much of an ethereal beam. The two men exchanged nervous glances.

Clayton pulled a writing box from the back of his coat. “Here. Write to us. There is paper and ink and candle. You must testify to the Friends, and to those who do not yet believe. Let them know of thy strength.”

Whitehead also reached into the folds of his coat and produced several bundles, which he transferred to the empty bag with the writing box. “We brought dried fruit and a bit of cheese from Ipswich. Smuggled in with a book or two and this.” He held up a small Bible.

James grinned slowly. “Now I have all I need. And I shall write. Though my words may be fewer now. I spend more time in prayer, and listening.”

“Write what thou hearest,” said Clayton. “And eat what you can. Put the rest into the cake box to keep them safe from rats.”

They heard the turnkey unlocking the door. James pulled at George’s arm while Clayton quickly tied the sack and lowered it down.

“Tell them, Friend George,” the boy whispered, “It is damp, but not as cold as Castle Hill prison. And I was made well from the Jail Fever by a visitation in the night. But for the lack of food I am stronger now than I was at court. Tell them.”

The turnkey approached, a look of worry on his face.

James patted George’s arm with all the urgency he could muster. “And thou must tell the Friends not to pay the fees. So much money can do far more good elsewhere.”

Whitehead responded as the two ministers gently tied the rope around the boy’s waist, “They know. Every new attempt to make the collection is stopped by thine own words from the courthouse.”

James nodded even as he was lowered down to the floor. They signaled a last goodbye, and Whitehead tied a scrap of cloth to the rope—a reminder that they had been there, that he was not alone.

Later that night, the wind howled outside the castle walls. Inside, young Parnell bowed his head in prayer, giving thanks for the many others who travailed on his behalf. Snow would come soon, and perhaps death. But for this moment, he’d had visitors. And more than that—he had been remembered.

He smiled faintly, “I feel them, like the warmth of fire through a closed door.” He looked around his little prison. “This is my cell of witness. The walls echo scripture. I will write a letter to the Friends. And another to the magistrates. Though they do not read them, I will write.”

He reached for his box, pushing a gnawing mouse away. Quickly to guard the paper, he pulled out a candle and flint. With the light came a greater hope. “I shall write, it is well with me. The suffering is nothing new. Christ met worse without complaint. I only pray I be not embittered by it.”

Carefully, he opened the little Bible and navigated quickly. “The third chapter of Lamentations,” he said, voice low but clear. “‘It is of the Lord’s mercies that we are not consumed, because his compassions fail not. They are new every morning.”

He lay back, nestling within the new blankets. “I would have that written on my heart, for when my mind grows weak.” He smiled as he planned his next epistle. “I will tell them that I go on faithfully. And that my chains are lighter than many men’s wealth.”

The Workhouse Game

Nightfall in the Cambridge House of Correction fell like a smothering hood—no stars, no sky, only smoke and stink and voices from the void and the growls of the mastiff ever at Vexler’s side. Tom spent his days hauling firewood up a stair that tilted like a drunkard’s gait, his fingers raw, the bottoms of his feet blistered from the warped planks that passed for shoes. He had not spoken. There was no one to speak to.

But the game found him.

He heard them first in the next room—low muttering, then a bark of laughter, not merry but cracked, like a pot dropped on stone. When Tom crept to the threshold and peeked round the frame, he saw them: two men crouched by a wall, just outside the torchlight.

The first was all elbows and ribs, a scarecrow in a cooper’s apron half-burned at the hem. His face twitched when he smiled, eyes darting between the shadows as though they might answer him. This was Cress, the barrel-maker, who spoke to nearby casks as if they were kin, and had once beaten a magistrate with a stave.

The second man lounged like a cat that had once drowned and come back different. He wore the remnants of a traveling minstrel’s coat, the embroidery long since rotted to thread. One eye gleamed like polished coal; the other was glazed and watery. They called him Lark, though his voice had betrayed him long ago, leaving behind a gravelly unmusical speech.

Between them on the floor was a small die, crudely carved from bone—human, by the look of it. The pips were gouged uneven, as though by a toothpick or nail.

Cress spied part of a boy peeking into their den and winked. “Deadman’s Chance,” he crooned, his voice almost musical. “Rules are simple. One throw each. Highest roll takes the stake. But roll a six,” he leaned in, breath rank with onions and loss, “and you name your penance.”

Lark grinned, lip curling to show a line of brown stumps that stood for teeth. “Tom-boy wants a go,” he croaked, looking up without looking at all. “Fresh as a church candle, this one. Let’s see what luck rides in his blood.”

Tom didn’t answer. He remained in the doorway, arms around himself.

Cress nudged the die toward him with the end of a broken stave. “Go on, then. No coin needed. Just the truth.”

Tom took a step forward. He didn’t know why. Maybe it was the way they watched him—not cruelly, not with pity, but like wolves too tired to hunt, curious what kind of creature had fallen into their den.

He crouched and picked it up, the die cold and smooth, with just enough heft to make it roll.

“Throw,” urged Lark.

Tom did. The bone clattered once against the flagstone, rolled, wobbled, and landed: a six.

A breath caught in Cress’s throat. Lark let out a soft whistle.

“Tell us, then,” said Cress. “What’s the one thing you would undo?”

Tom blinked.

He thought of Bess. Of the smell of clean linens and yeast, of her hand on his hair and the way she hummed under her breath as they scrubbed his cell walls together. He was surprised to note a longing for that space, that privacy, even if he’d begun talking to himself a little. Now even that voice was gone.

He thought of James, still locked away in Colchester. Of his defiance at court. Of the way he had smiled at Tom that first night in the cart.

He thought of himself, hollowed out and trembling.

“I should have said no,” Tom whispered. “When they came for us.”

Lark’s good eye narrowed. “Too late for that, boy. We all should have said no to something.”

He reached for the die and tossed it. A three.

“Saved by a hair,” he muttered. “Cress?”

The cooper rolled a five, then began to laugh.

“Well now,” said Cress, standing and brushing his knees. “It seems our penitent lad wins the night.”

“Wins what?” Tom asked.

Cress winked. “Not a thrashing, for one. Maybe a crust of bread if you sit near the kitchen vent. Maybe not being seen.”

Lark stretched. “Or maybe you win nothing at all, and that’s the best you can hope for in here.”

The light shifted as a warder’s lantern passed somewhere beyond. Tom didn’t move. The die lay on the floor like a relic from some ancient rite, carved from the dead, rolled for the living.

Deadman’s Chance.

In the silence that followed, the game dissolved, and Tom felt the air tighten again, thick with dust and damp and the quiet breathing of men whose lives belonged to Vexler, and his house would be their grave. He stood, turning toward the stair. He didn’t want to stay. But he wasn’t allowed to leave.

A Midnight Walk

It was All Hallows Eve, a celebration banned yet marked in the hearts of those who were accustomed to remembering the souls of the departed with religious deference. For Tom and his fellows it was another unpleasant night when a body wanted to lie below ground as the bitter cold rimed the world above them.

He slept in a cell with a dozen other inmates, snoring lightly in spite of the roaring sounds emanating from his near neighbors. At the watch change the door groaned on its hinges, and a new figure stepped into the room…heavier-footed than the usual guard; slower, menacing, and radiating coiled force. Certain prisoners who tended to be wakeful shifted in their straw, quieting.

Lark caught a glimpse and muttered, “That ain’t Vexler.”

Cress grunted. “New meat?”

“No,” Lark whispered. “Castle Hill. I know that walk. That man’s cracked ribs for less than a cough.”

The newcomer’s bald head caught the lantern light. Scarred knuckles, jaw set like quarried stone. Duffy. Even the mad ones knew to hush.

He moved across the stone with measured menace. But when he reached Tom, he paused.

“On your feet,” he growled, kicking the boy soundly in the backside.

Tom’s legs protested, but he stood.

Duffy opened the door and shoved him—not unkindly—down the passage, steering him toward the darker end where old boards creaked underfoot and the torchlight faded.

“Five minutes,” Duffy murmured, grabbing the boy’s arm and half-dragging him in case there were any watchful eyes. At last they reached an enclosure where a guttering candle provided some light. The jailer crouched down and pulled his hood back to reveal the old broken nose and an almost kindly grin.

Tom blinked. “What?” Then recognition flamed within him and he wanted to shout. The man chuckled slightly but then with a stern look held up a finger of caution. The stones had ears in this place.

“I’m your jailer tonight. In for a friend who remembers what it was to celebrate Hallowtide before them Puritans held sway,” he winked. Then another miracle—he held forth a small biscuit. Tom checked Duffy’s eyes first to be sure he might have it, then grabbed the morsel, gobbling it down like a fiend. It wanted more, but he savored the taste of real food in his mouth.

Licking his lips, Tom asked the first, the overpowering question in his mind. “Bess?”

Duffy busied himself, dusting off the mouldering hay from the lad’s shoulders, avoiding his eyes. “She saved Pip, boy. Got him away from Thresher.”

Tom was gobsmacked. It was as if he was walking in a lovely dream. To know that his friend-slave was free, unthinkable. As a child born at the prison to a mother dead even before he drew breath, his was a life sentence of servitude.

“Aye. Fever nearly took him, and Thresher cast him on the rubbish heap. The rubbish heap, Tom. What kind of devil does such a thing? But as Bess was gathering up your precious items—for you know as I saved ‘em, Tom, hid ‘em I did behind a post until we could rescue ‘em from Thresher, since he’d sell ‘em quick as anything.” He counted slowly on his fingers, knowing the boy was wishing, absolutely dreaming for another morsel of food. “She got your blanket, your bowl and cup, all of it. And then as we was sneakin’ away, she heard the lad cough and made me put ‘im in the back of a wagon with ‘er. Paid for it, though, poor lass. Sick again. Can’t walk some days.”

Tom’s throat clenched. “Where is she…?”

“Blakeling’s got ‘er, though not in the ‘ouse, o’course. And Pip carnt be anywhere near, as he don’t like ‘is lice. Also…I’ve got to tell you, lad…Eleanor Blakeling, she’s in prison. And both Georges at the moment. Carnt keep their mouths closed, can they?”

Tom blinked, taking it all in with a great sadness.

“But the boy’s at mine, lad. Yes, Pip keeps the place tidy fer us. Bess comes by as can, though not so much now. But she taught Pip a bit o’ baking. He makes little oat cakes like this ‘un.” Here he held up another morsel which Tom happily grabbed and gobbled right down. “Sells ‘em near the bridge two-a-penny. Can you believe it? And he sends these special just for you.”

Here Duffy revealed a small packet of the cakes, which he transferred between hands before Tom could snatch them away. “Careful, lad. Don’t put too much on a stomach long empty. You remember, don’t you?”

The boy looked up forlornly and nodded. “I’ve not known hunger like this, though, Duffy. Even if I find a crust I must save it to rent a cover at night or something to put on my feet in the morning.”

The jailer had hidden the little parcel behind him, to make the boy pick a hand, but he brought it out instead and wrapped it in a rough piece of cloth which he then tied across the boy’s chest like a sash.

Tom swayed where he stood. The cold stones felt less cold.

“Now listen. You want to watch Vexler, boy,” Duffy muttered low, with a sideways glance at something like a shadow down the way. “He ain’t loud, not like Thresher. Don’t bark, just watches.”

Tom nodded, now following Duffy’s gaze down the hall.

“That man’s got a ledger in his skull—puts down every wrong thing you’ve done and waits ‘til you’re tired, hungry, or near dead to collect the debt. You steer clear. Don’t owe him nothing, right?”

Again the boy nodded, patting the biscuit and thinking of his endless hunger. A mouldy crust could be surrendered without much sorrow, but these reminders of his life before—real food—he wanted them more than anything.

Duffy stood. “We’ve got to get back now. There’s two I know was wakeful, and you don’t want to trifle with ‘em, Tom.”

“Wait. Duffy, I have this,” the little prisoner whispered. “You can give it to Pip from me.”

Tom pulled a leather tie from his hair, revealing locks that reached below his shoulder blades. On the tie was a bone die he’d been shaping, its marks precise, sides smooth despite the crude tool that had made it. He pulled it off the cord and held it up to his friend. Duffy examined Tom’s work and nodded appreciatively, leaning back against the wall to catch the bit of light.

“You make this yourself?” He looked at the boy, searching for a lie or half-truth in his face but finding none. Rather, Tom had become shy, as a lad who’d received an embarrassing compliment. Satisfied, the man nodded. “Well done, boy. If I’d known o’this talent I’da had you making me bits ‘n bobs for me own pay. That Vexler’s got a taste for ornament, though. Things with edges and curves. Had a boy last winter carve him a snuff-box, and it got the lad kitchen duty for near a month—which around here passes for a mercy.”

He held it back to Tom, who quickly declined it. “I can make another, Duffy. It’s as easy as anything.”

“Oh, you make me rue me own negligence. I’da had a good market goin’ in these, mind.” He pocketed the piece and stood up straight. “Right. Then make another to give Vexler, but don’t do it soft-like. Make it a trade. Make it his idea, see? Vexler don’t trust kindness. Thinks it’s a trick. But he does believe in money. Always did like pretty things he could sell off for a penny more’n they’re worth.”

Duffy looked hard down the hall at retreating shadows, voice rising to his usual bark for the benefit of any still within earshot. “Move along now, rat!” he growled, grabbing Tom by the collar and giving him a shove that was more pantomime than punishment.

Already back within the cell, Lark and the cooper shared a knowing glance, the former spinning his bone die with one finger and giving a wink as if to say, ‘Dead men play long games, lad.’

In the corridor, Duffy’s voice dropped lower as he bent to growl one more instruction. “Tell no one about our alliance. I’m not here for kindness, mind ye.”

A few steps further and he shoved his young prisoner roughly into the cell, slammed the door, and resumed his slow patrol, every step a threat. Inside, Tom rose from where he’d landed, tying his hair back again. Lark, pretending sleep from beneath a pile of sacking, reached out to grab an ankle. Yet the boy was too quick, skipping over the slumbering group and taking refuge in a corner behind a heavy snorer who was known to pound on any who disturbed him, without even fully waking. Cress lifted himself on one arm and Lark pointed Tom out. The two consulted in whispers even as Tom weighed all the news that had come to him like messages from the living to the dead.

The Chains of Colchester

November, 1656

There was a smell of damp straw in the courtroom.

It issued faintly from under the benches where piles were meant to capture the gray sludge that trickled in from the narrow lanes of Colchester, mingling with the sour reek of damp wool and unwashed cloaks, as if the floor had been swept with mildew instead of broom. George Fox the Younger noticed it at once—before the rustle of papers, before the rattle of a clerk’s inkwell and the vinegared scent of ink, even before the cough that echoed like a musket shot in the gallery. It reminded him of the stable in which he had once hidden from a pursuing crowd, and of the floor of Lancaster Jail, where he had met with George Whitehead before his transfer here.

Colchester Castle squatted behind this chamber like a waiting mouth, ready to devour the condemned. The courtroom above it was plain, lit poorly by gray daylight leaking in through the high-set windows. A judge’s bench rose at the far end, draped with a threadbare green cloth, where sat Justice Elias Wroth of Suffolk, dressed not in wig and scarlet, but in the sabled cloak of Cromwell’s era. His stern face looked out grudgingly under grizzled hair, with brows that had forgotten how to lift in mercy.

Fox entered the courtroom with mud still on his hem, his shoes soaked from the fields, his eyes bright with rain and something harder than rain—certainty. This in spite of his uncertain ground, for he came not as a petitioner, nor as a man summoned by law, but simply as a man who would be heard.

He had walked from Ipswich, where he had spent the night among Friends in prayer. For a new crisis had emerged. One James Nayler, a Parliamentarian soldier in the war, a gifted and charismatic preacher, and an otherwise bright and kind Friend—indeed, second in command to Fox himself—had done the unthinkable down in Bristol.

At the end of October, the man had made a public display, riding upon a horse into Bristol as several women laid blankets before him crying “Hosanna!” They were arrested immediately, and news of it went out across all of England, Europe, and the Colonies to call down fury upon the Quakers wherever they might be found.

Young Fox hoped to testify on behalf of the defendants and all Friends. They were not Nayler, and at this moment, Nayler was not a Friend.

“Another one,” someone muttered, pointing to Fox’s hat. “Same as that fellow in Bristol—think themselves equal to the Savior.” The whispers passed like a breeze through the room, thickening the air of judgment.

The court was not in recess, nor open to visitors. The air in the gallery bristled as the doors shut behind him.

A clerk stood immediately. “What business have you here, Quaker?”

Fox moved forward, unhurried. “I come on behalf of George Whitehead, and the others held with him without just cause.”

Wroth snorted at his table and responded without a look. “You were not summoned.”

“Yet I have come,” Fox responded, his voice echoing across the room.

The judge’s eyes flicked up. “Indeed.”

A whisper travelled around the seated petitioners and respondents, those who had been summoned and belonged to the proceedings. The judge looked through the group.

“Which of you is Fox?” he asked.

“I am George Fox.”

“You are not the one who was in Launceston?”

“No, he is our founder.” Fox’s tone was even. “I merely bear the same name.”

The judge’s lips thinned. “I see. You look nothing like I would expect of this George Fox I’ve heard so much about, yet like him and his fellow who has made himself notorious, you have mistaken your own importance.”

“I mistake nothing and speak not of myself. George Whitehead is held in Colchester Castle for what good reason—speaking in a steeple-house? For praying among Friends? There are charges but no crime. Let the record show I ask for his release.”

“You ask,” the judge said, letting the word rest like a shilling on the bench.

“I do.”

The courtroom was still. Behind Fox, a clerk shifted uncomfortably. The magistrate’s associate whispered something to the judge, who waved it away.

“And are you his counsel?”

“I am his friend.”

“That does not qualify you to address the court.”

Fox took another step. “Justice does, for I attest to his character and to his—and all of our—complete separation from that one man who has erred. He is not the measure of our faith, nor are we bound to his mistake.”

It was not a shout, but the words carried. The judge sat back and considered him, but twenty-three years old, the scruff still upon his chin. A moment passed.

“Young man,” Wroth said quietly, “you speak in my court as though the world were waiting to agree with you. It is not. The world is exhausted with your Friends and if they do speak of their sufferings, they ask for a firmer hand to put an end to the blasphemies practiced in every steeple-house, in every parish.”

“I only ask to provide testimony,” said Fox.

Wroth turned to his clerk. “Bring me the letter. The one from the woman in Bury.”

The clerk rifled through a pile of paper until he found it—a folded sheet with the seal broken.

“Here is testimony,” he wafted it before all and sundry, “written in her own hand, if you will believe it, by a woman called Margaret Sutton. You’ll know the name, perhaps.”

“I do,” Fox said. “She attends the meeting in Bury. And suffers for it like the rest of us.”

“She writes,” the judge continued, opening the paper with distaste, “that she will lay down her life if it will spare Whitehead’s.”

He read aloud, in a voice raised nearly to a woman’s tone, speaking with contempt:

“‘If there be a sentence, I entreat it fall on me, for he is young and full of God’s light, and I am old, and ready to depart.’” He looked up. “And what would you have me do with such a letter, Friend Fox? For she sounds all the world like those mindless women who shouted their praises of Nayler and suffered for the same.”

“Believe it,” said Fox. “And tremble.”

“I tremble,” said the judge, “only at the madness infecting your sect. Do you take me for Pilate, to grant mercy by the mob’s request? I see no repentance in Whitehead. Nor in you. All of you are as disturbed or dare I say devious as this Nayler, who made himself a Christ.”

“None of the defendants were about when this one man acted so ill.” Fox answered. “We will not recant what we have not done wrong.”

The judge’s voice raised to a thunder, “You persist in speaking as if this is your chamber!”

“I speak,” Fox said plainly, “because others are silenced. You beat them and gag them and hold them below the ground, and call it justice.”

At this, the judge rose, standing at his full height—a remarkable six feet—still powerful though aged. He slammed his hand once on the bench.

“I have given hearing,” he said, “when I might have ordered removal, especially in the light of recent events. I have read the letters. I have tolerated the filth that issues daily from the mouths of your people, and what have I received in return? Insolence! Women on my doorstep! Raving tracts on the blood of Babylon! Do not mistake my patience for lack of power.”

Fox stepped forward again, dangerously close to the bench. The bailiff stepped before him and pounded down his stave. As the echo of it faded, the young man continued, “We are not asking patience. We are asking righteousness.”

“And I am telling you,” the judge said, voice rising, “that if Whitehead is righteous, then righteousness smells of horse piss and stale bread, for that is what I smelled when I last passed his cell. You worship the gallows and call it glory; if that is your inner Light, it shines dim indeed.”

The courtroom shifted—some smirked among the lawyers and petitioners, all having received the news of Nayler as a threat to their daughters and the women of their towns. Yet the Quakers’ willingness not only to endure punishment but to call themselves martyrs was even more unsettling. How much more verbal sparring might this judge tolerate—and where lay the punishment for one such as this?

Fox took a breath. “The world,” he said, “has always confused the prisoned with the guilty. That is your error, as it was Pilate’s.”

A silence descended. Now would the axe fall on such impertinence.

The judge leaned forward and spoke softly. “Young man, I did not allow you to speak because I knew you would not beg, but because I hoped you might listen. Now I see you will not. Very well.”

He turned to the clerk. “Contempt. Add his name.” “On what charge?” Fox asked, almost gently.

“Contempt of court. Arrogance before the bench. Disruption of session.”

“Are those crimes?” Fox asked.

The judge said nothing.

A tap came at the side door. A soldier entered, summoned by a nod. He moved to take Fox by the arm.

Fox looked at the judge. “Your Honor, you may shackle my body, but the chains that bind you are heavier.”

Then he turned, and let the soldier take him.

The courtroom was full of whispers and a few carefully launched cries of, “Blasphemer!” George did not resist. He walked calmly from the chamber, through the echoing corridor, past the cold stones and dripping torches of Colchester Castle’s inner passage, before descending beneath the earth.

The courtroom resumed, but its air was changed. Damp straw still lay in the corners but now it smelled of more than mildew and rot. It smelled of a name added to a list. A silence that had spoken. A law that had failed to silence.

And in the farthest cell, among the old stone and broken pails, George Fox the Younger sat down beside his friend George Whitehead. He had done nothing but sit and speak, yet the stain of Nayler clung to them all. Whatever one Friend had done in Bristol now marked every Friend in England.

They sat in silence, entrusting themselves to God and grieving for the one who had fallen.

In the days to come, the letter from Margaret Sutton would find its way into other hands—copied, carried, and preserved. The record of one woman’s plea. The cry of a man unbidden who dared to enter where he was not called.

The law had spoken. But not last.