It was near dusk when Bess came, though neither Duffy nor the boy believed she’d manage it. The wind had been fierce all day, rattling the loose clapboards at the rear of the yard and carrying with it the odor of spent coals and pig offal from the butcher’s slope. The door banged twice before Duffy reached it. He nearly asked who dared knock so late, only to see her already bracing herself against the lintel, breath shallow as if she’d walked from the churchyard itself.

“God’s wounds, Bess,” he muttered, more prayer than profanity. He made no show of helping her in, only stepped aside so she might cross the threshold on her own power. She did, but with a small, sharp sound as her weight shifted off the stick she carried.

“You’d have left your supper to that child,” she rasped, nodding toward Pip crouched before the hearth. The boy watched her with wide, shining eyes. “I have seen his pot boil over twice this month. And not a soul taught him to keep salt from flour.”

Duffy kept his arms folded, though the motion only emphasized the pale scars at his knuckles. “We manage,” he said, soft but defensive. “He’s not starving.”

She ignored the tone, turned her attention to the hearth. The fire was smothered with too much green wood—a sign Duffy was spending Pip’s money on strong beer instead of decent logs. He didn’t mind a poor hearth to drink by. Another argument they’d had too often.

The pot itself was perched askew on a brick. She surveyed it as though she might catalogue every failing in a ledger and submit it to Heaven for judgment.

Pip rose, wiping his hands on the apron she had sewn for him in a better season. “I tried to make the batter,” he told her. “But—”

“It’s not batter,” she said gently. “It’s glue.” She set her stick aside and lowered herself to a three-legged stool, retrieving the cloth that was always tucked to her apron so she could pull the pot closer. Her breath rattled in her chest as she lifted the spoon. “Fetch me the sack of barley. And the salt—only a pinch, mind you.”

The boy obeyed at once. Duffy found he could not look at her hands—knotted, bruised, rimed with age—without feeling something uncomfortably like regret. He turned to the shutter, adjusting the latch that never stayed true, but his attention strayed behind him with each movement she made.

“You shouldn’t be here,” he said at last, not turning. “The doctor—”

“—is a prattling fool,” she finished. “And a costly one. I have a short time left to me, and I will not spend it dying in that cot.”

Her tone had the shape of old defiance, but no strength behind it. The words trailed off into the rasp that had begun in the spring, when the first coughs tore through her and never let go. Duffy swallowed, jaw clenching. If she died here—under his roof—it would be one more burden he’d never sought. And yet he felt a strange, ragged gladness to see her upright and scolding, her presence more potent than any sermon.

She worked in silence for several minutes, instructing Pip in a thin voice that barely carried over the hiss of the boiling water. He measured and stirred, eyes flicking up every few heartbeats to be sure she still watched.

“‘ere, lass. Drink some’at.” Duffy handed her a cup with a little weak cider. She looked up at him and nearly smiled, their fingers brushing as she took it from him. A shiver passed through her frame as she drank. Lowering the cup, she swallowed with difficulty, and pressed her lips together so tightly that the lines at her mouth whitened.

“Bess,” Duffy said again, voice low, “ye don’t need to worry—”

She handed him the cup with a look, and for a moment it was not the quarrel they’d nursed these many years, nor the weariness, nor the unshed recriminations that passed between them. For a heartbeat, they were only two souls who had outlived many others of their age. The old hearth flickered with the firelight, and he had the impulse—shocking in its unfamiliarity—to kneel beside her and set a hand over hers.

But the moment turned as swiftly as it came. She shook her head, dismissing him, and reached over to wipe the rim of the pot. As she did, her breath hitched. The cloth fell to the floor.

“Bess?” Pip whispered. He caught her elbow as her weight listed to the side. She made a sound—half gasp, half sigh—and her eyes rolled back. Her head struck the edge of the stool as she collapsed, her stick clattering away across the boards.

Duffy lunged then, catching her before she could slide to the hearth. She was shockingly light. He held her under the arms, bracing her against his chest. Her hair smelled of lye soap and stale herbs. When he pressed his palm to her cheek, he felt the cold that had been waiting all along.

“Fetch my blanket,” he ordered Pip. The boy scrambled to obey, dragging a thin wool coverlet from the cot and pressing it into Duffy’s hands. He arranged it around her shoulders, heedless of the flour dust streaking her bodice. His throat worked as he swallowed, his own breath unsteady.

“Bess,” he said, not caring now if she heard the rawness in it, “if you can hear me—”

Her eyelids fluttered once, twice, and settled. The rasp of her breathing continued, but slower, each exhalation ragged as though the spirit were being torn from her inch by inch. He held her upright, feeling the fragile rise and fall against his chest. He thought she might weigh less than the chain he carried at his belt.

The pot still simmered on the hearth, untouched.

Outside, the wind rose again, rattling the shack until Pip pressed himself against the wall and shut his eyes. Duffy did not move, save to shift his grip when her head lolled. At last, he looked down at her face, searching for any sign she would rouse and scold him for being soft. There was none.

The moment stretched until the fire burned low. He had lived a life accustomed to waiting—waiting for sentences, waiting for rations, waiting for release. But this waiting was worse, because it had no certain end and no justice at its conclusion.

He wished she had saved her strength, left the batter glue and the boy’s mistakes uncorrected. He wished she had chosen any place but here to surrender the last of herself.

But above all, he wished she had not come, because now he could not pretend he was unaffected. He was not a turnkey tonight, nor a man paid to keep order among thieves and dying paupers. He was simply the last witness to her last act of making something useful in the world. And that was a weight he did not know how to lay down.

When she stirred faintly, as if to rise, he tightened his hold. “Stay,” he murmured, voice gone hoarse. “Stay a little longer.”

But her breath did not change. The thin rattle continued, steady and merciless. And he knew it would end before dawn.

The rattle of her breathing slackened by imperceptible degrees until each pause stretched into something Duffy’s mind refused to name. He kept his hand pressed to her cheek, feeling the faint pulse fluttering at the hinge of her jaw. His thumb brushed an old scar there, a small seam of whitened flesh she’d earned lifting a kettle that had slipped—twenty years gone now, or more. He could not stop thinking that if he could feel that scar, she was still here.

Pip crept nearer, barefoot, hugging his elbows. The boy’s face was the color of unbaked bread, his eyes so wide it seemed they must crack from the strain. “Is she—” he began, then swallowed, voice thinning. “Sometimes they sleep like that. Old Jenny, she slept two days before she went cold.”

“She’s not asleep,” Duffy said, though the words lodged in his throat like a swallowed bone. “She—” He could not finish it. He leaned close, so close he could feel the last wisps of her breath against his mouth, as if she were trying to whisper something final.

The fire shifted on the hearth, the logs collapsing into a flare of sparks. In that moment, she exhaled with a hollow, final sound; a little sigh that had no answering breath. He knew it before he felt the change. Her weight seemed to alter all at once, slackening in his hold, as though whatever invisible tension had kept her tethered here had been cut. He had lifted bodies before, living and dead, and he had never been mistaken about the instant the soul departed. It was the simplest thing in the world. Just a subtle reordering of weight—something solid becoming empty.

He gestured for Pip to hand him the cloth now just beyond reach on the floor. The boy obliged quickly but questioned it. “Her own cloth for a ghoul-rag Mister Duffy?” He looked nervously at her face as if she might open her eyes in fury at the thought. Yet they remained still and the boy realized all at once there would be no more chidings, no more guidance from the old woman. More like angel now.

He pressed his knuckles to his mouth as a single tear tracked the flour dust on his cheek. “Mister Duffy,” he said in a small, frightened voice, “do ye throw salt as Thresher does to send the spirit on?”

Duffy did not answer at once. He was staring at her face, feeling a strange pressure at the back of his skull, as though the knowledge was too large to fit. The lines that had furrowed her brow rested, her mouth no longer compressed in worry. She looked younger in death, as if the years had slipped free with her last breath. He quickly tore the linen and held her chin tenderly closed while he tied a soft knot above her head, almost in a fear of seeing in her the unhandsome ghoul. No, she must stay like this in his mind, always. As she might have been had they met early and grown old together.

Pip sniffed and reached for the little dish of coarse salt by the hearth. He seized a pinch, his fingers trembling, and turned his back to her body. “I’m doing it,” he whispered, more to himself than to Duffy. “I’m sending her safe home.”

And before Duffy could tell him not to bother, the boy flung the salt over his left shoulder. It scattered like frost across the hearthstones and the two lying together in silence. The moment was as complete as any church funeral.

Duffy drew in a careful breath. The taste of woodsmoke and salt filled his mouth. He whisked away the white grains and shifted Bess’s body to rest against his knee, cradling her as gently as a child. He realized, distantly, that his hands were shaking. All the clamor of the last three years—the curses and bargains and his iron ring of keys—seemed to have been left outside a door as real as any and larger than most. All of it replaced by this single, immutable truth: She was gone.

Pip dropped to his knees beside her, pressing both palms together in an awkward, crooked prayer. “Don’t haunt us,” he murmured. “You done enough good. You go on.”

Duffy let his head bow, the cords in the back of his neck aching. He could not have spoken if he tried. For a moment, he simply held her there, feeling the last warmth leaching from her skin. He thought of all the times she had scolded him for neglecting the small mercies—fresh bread, a proper blanket, a kind word—and how often he had answered her with silence. And now there was no time left to make a change.

The wind rattled the shutters again. The fire sank lower, revealing the dull shine of the spilled grains. It looked like a boundary drawn across the floor. He almost envied the boy’s certainty that it meant something, that some ancient bargain could be struck with a pinch of salt and a whispered plea. He had lived too long to believe in such comforts. And yet, holding her in his arms, he wished he could.

Pip drew a sleeve across his eyes. “What do we do now?”

Duffy swallowed, his mouth dry as ash. “We lay her down.” He spoke low, rough. “One of us will have to go to Blakeling. He’ll wonder after her.”

The boy nodded, though he did not rise. Instead he reached out, his small hand hovering above her brow. It hovered there an instant, then withdrew. Duffy lowered Bess’s body to the boards, arranging her hands over her breast. The movement felt strangely ceremonial, though he knew no proper rites. He only knew she deserved better than to be left crumpled like a fallen sack.

Finally, he unbent his body and stood, bracing one hand on the edge of the hearth to steady himself. His joints cracked. His chest ached as if a rib had splintered inside him. He looked once more at her face, memorizing it—wishing he could believe, as Pip did, that she was already in paradise.

The boy’s voice trembled in the dark. “Mister Duffy…if she comes back—”

“She won’t.” He meant it as reassurance, though in that moment everything about the man that had been a comfort to Pip—his strong, protective nature—had dissolved into a deep sorrow.

At last Duffy looked up at the boy. “Do you want to take the message? Or I can go if ye like.”

Outside, the last daylight was draining from the yard. Night pressed up against the cracked panes of glass. Pip felt a horror at staying alone with the dead—particularly at night—and with Thresher there had never been an option. In another moment he’d wrapped himself in a blanket and disappeared up the street.

Duffy picked up the walking stick she had carried in and set it beside her folded hands. He almost laid his hand to her cheek again, but stopped himself.

With an effort, he drew a long breath and turned to stoke the fire, preparing for a night’s wake. The pot still steamed, no longer containing glue but a congealed mass. He removed it from the hook and set it aside. Then he gave his attention to arranging the logs and bringing more to keep the room bright for any who might come; and he supposed there would be some who laid a greater claim to the lass that his, even with the boy Pip being her favorite son, as she sometimes said.

This chore done at last, Duffy stood over Bess’s body and allowed the hush of the room to settle around them like a burial shroud.

All in a moment, Pip swung the door wide for John Blakeling. Rain slicked the night behind them, and in the lamplight stood the master, hat in hand, his dark cloak dripping at the hem. Beside him was a woman of perhaps thirty, red-brown hair pulled back severely. Her gown bore the dust of kitchen work, but she stepped inside with quiet poise, holding a covered bundle of linen.

“She’s gone, then?” Blakeling asked.

Duffy did not look up. “You’d not be here otherwise.”

John’s eyes moved to the still form. “The lad caught us as we were closing the house for the night.”

Pip, suddenly shy, looked at the floor. “I thought you’d want to know, sir. She was gone too long.”

“I would have wondered come morning.” he nodded slowly. “And she’s no longer mine to account for, I suppose.” His voice was tight but not unkind.

The woman stepped forward, laying her bundle on the small table. “I am Minta,” she said to Duffy, as if introductions still mattered.

Duffy nodded numbly. “She said you’d come to help as the Missus is…er…indesposed.”

John’s lips tightened, for as kind as Duffy had been, he yet represented the system that now held his wife without mercy. “Imprisoned as thou knowest. Yet there is hope for release soon.”

“Not to be disrespectful, marster, but I’m hoping it will not be the same kind of release what Miss Bess has had.”

Minta quickly set herself up near the body and directed Pip to get water, clucking away, “I did say, didn’t I, to stay abed, but she would have none of it but to come see her Mister Duffy and Pip.”

Duffy finally looked at her. “You knew she’d come here?”

“She spoke of it every day. She would not die in that house, she said, but that she must come first to see thee. Had I stopped her, she’d have climbed out the window.” Minta gave a faint, rueful smile and opened the cloth bundle to reveal a length of white linen, soap, a small pair of shears.

“She served your house a long time,” Duffy said to Blakeling.

“Longer than some who bore my name,” he replied quietly. “She taught my daughter to sew. And to throw a clod at crows. What she loved, she ruled.” He looked again toward the cot and other fittings in the room. “I’ll see to her grave. I’ll not have her buried like a stray.”

Minta was already setting a pot to warm water over the rekindled fire. Pip stood back, arms wrapped round himself, as if unsure whether he was child or man in this moment. Duffy reached out and pulled him to the bench beside him.

“It’s all right, the best thing’s being done now,” he murmured.

“She’s cold already,” Pip whispered.

“I must bathe her now,” Minta said, glancing at the men who all seemed deep in thought, without recognizing the delicacy of the situation.

John harrumphed and looked for another place to stand, though finding few options.

Duffy jumped up, taking Pip with him. “We’ll clear the table.” He took possession of the small cask of ale and his mug that had awaited dinner, pouring a drink for his guest as the boy worked.

“A drink, Marster Blakeling.”

The Quaker shook his head politely, but took the moment to teach, “Thou hast no need for titles, Duffy. We are all equal in God’s eyes.”

The old jailer drank deeply before responding, “I am not of a mind as yet to enter any particular religious camp, sir. But I am glad of your kindness, and glad for her sake that she got a happy life in your household…” As he paused, John acknowledged his gratitude, before being caught by his last sentence: “…I reckon she knew where her peace was, though. ‘ere with us.”

Minta coughed lightly as she draped a clean cloth over Bess’s face, then stood to open a large piece of linen. “I’ll ready the table then.”

She completed the job Pip had done rather poorly, wiping away the remaining flour and covering the whole gracefully. She waited then, eyebrows poised expectantly.

Duffy was yet finishing his mug of beer, and John was obliged to motion Pip over to the body for the purpose of lifting her to the table.

When Bess was settled, Minta continued. “She may be viewed, if others come. But not too long. She must be buried on the morrow, before the flies.”

“I’ll send for a cart in the morning,” Blakeling said.

“No cart,” said Duffy. “We seen too many death carts in these years of plague and war, piled with who knows what bodies from who knows where. She’ll go in a funeral barrow, with respect. I’ll push her myself.”

John might have responded something about being all the same to God and man, in particular after death, but instead looked at the jailer, and the silence between the men was thick with something too old to name.

Then Pip, small voice trembling, asked, “Do I throw salt again? Is that how you send a ghost back home, Minta?”

The woman smiled gently. “That’s for old houses and bad dreams, lad. This one won’t linger.”

“None of our spirits linger, Pip.” Blakeling spoke a bit roughly, for he was tired. “The Light is in us, and it belongs with God. Bess is now with her Lord.” He glanced at Minta and the two visitors made their farewells.

After the door was bolted shut, Duffy refilled his mug. “You take the cot, Pip. I’ve no need of it.”

“Are ye sure?” He’d not laid on a bed since recovering from his illness. And the courtesy of it even while he was at death’s door was a hard-won victory for Bess.

“Aye. Have the cot, then.” Duffy sat on a bench against the wall. “I’ll keep watch tonight.”

A King’s Crown

March, 1657

The sky was not yet light and Oliver Cromwell settled at his desk, unlocking a drawer to retrieve a blotched parchment left there the night before. He had not slept. Wind gnawed at the mullioned windows and whistled through a gap near the lintel, stirring the edge of a map weighted down with the agate pawn. He pulled an oil lamp close to review the text for the thousandth time.

The fire behind him had been revived by a silent steward who now crouched like a sleepy shade in the corner. Cromwell made no sign of acknowledgment. A tin pot of strong coffee had gone cold by his elbow. Twice he reached for it and twice left it untouched.

The parchment bore a crest and the scribal polish of the Instrument of Government’s successor, a document many thought would name him king. Parliament’s offer, made on the first of March, was now nearly a fortnight old, and still he hesitated.

It was not conscience that slowed him, nor ambition—at least not in the vulgar sense. The weight he felt was that of Law, the People, and Providence, all pulling in opposite directions.

He had purged one Parliament. Dissolved another. And now the Parliament that remained asked him to be monarch, as if he had not spent the last decade tearing monarchy apart root and branch. A dry laugh escaped him. What kingship could he wear that Charles Stuart had not already soiled?

The door creaked.

“Father,” came a voice he well knew. “Thou ought not begin thine days without counsel.”

Charles Fleetwood stepped into the chamber with rain on his cloak. He brought no umbrella—he never did—and the cold clung to his boots. In his thirty-eighth year, the man still held the look of a soldier, and yet there was something more priestly in his manner this morning. He bowed slightly, closed the door behind him, and moved to the hearth without being asked, taking the moment to speak in the familiar tones they used within the family.

“Wouldst thou like me to warm thine brew?”

Oliver glanced momentarily at the pot, still steaming beside him. “Thou jests, but the drink is good. And we shalt have another coffeehouse soon. I have spoken with Thomas Garway of his plans for one in Sweetings Rents, across from the Exchange thou lovest so well.”

The Lord’s deputy seated himself by the desk with a genteel air that set his father-in-law’s nerves, holding his walking stick to one side as he might a scepter. “Thou seekest to promote the drink from thine friends the Jews—”

“Stop.” Cromwell held up a hand. “I do not make them friends—and perish that word in itself for the Quaker meaning, but I do see them as brothers to Christ.”

Charles reacted to this, “His killers you mean.”

“His family—and the inciters to kill were the pharisees, the lawyers of their time.” He glanced up with meaning. “The disciples were Jewish. The first Christians Jewish…is it not written, ‘Salvation is of the Jews’?” He stopped himself with a sigh of exasperation. “The drink brings health, which I seek. I commend it to thee as being far better than beer to accompany thine daily meals.”

“The coffeehouses are no bath houses, father, and they are not frequented by old ladies with bunions. They are full of men reading, exchanging, and discussing their pamphlets and broadsheets.”

“‘Prove all things; hold fast that which is good.’” Cromwell held up the edge of the parchment with irritation. “I have more important things to absorb my thoughts. Art thou aware of this—and the terms?”

Fleetwood nodded, frowning. “I have heard it discussed, in detail.”

“And what dost thou hear at the Exchange?”

“‘A crown by any other name’ and so on. Some say it offers the promise of orderly succession…if thou shouldst feel the need of it.”

“Succession,” said Cromwell. He sat back uneasily and touched the paper before him, not to read, but to feel its texture. “I shall live to see myself embalmed.”

“Thou wilt live to see a son in power, if thou wouldst see it signed.”

That drew Cromwell’s eye. He turned his whole body with effort and fixed Fleetwood in a stare so penetrating his deputy shifted his weight.

“There is only Richard. A good, God-fearing son. Loyal. Richard fears God, but the Lord has not ‘taught his hands to war’ nor his fingers to fight. And this…” he held up the parchment by the corner again; higher, as one might hold a noose, “this is battle by pen.”

Fleetwood allowed a pause. “I do not speak against thy son, only of this ‘realm.’ We cannot crown thee and then wonder who shall wear it next. They will take it from Richard the day thou art in the ground.”

Silence. Then Cromwell spoke, as if to toy with his son-in-law. “Thou thinkest me near death?” He smiled to himself as he pretended to study the page. “‘An inheritance may be gotten hastily at the beginning; but the end thereof shall not be blessed.’”

Charles, to his credit, did not flinch. “I think thou hast been ill every month since Christmas. And I think Parliament believes so too. They do not crown a man they expect to reign for decades. They crown a keeper of the seat until another may claim it.”

The Lord Protector turned back to his table, breathing steadily out with the pain of motion, as though the leather cushion itself offered no peace. He reached for his coffee again and stopped. “Better they crown a corpse. Let them take my skull to Westminster and set it on the throne. It shall sign what I will not.”

Fleetwood half-smiled. “The crown does not suit thine head. But neither does it suit the children of Charles Stuart. That is what they fear.”

Cromwell’s eyes narrowed. “Then let them fear the Lord, not men. ‘Put not your trust in princes, nor in the son of man, in whom there is no help.’”

They were interrupted by the sound of clerks chattering, entering by an inner door before they stopped and held a collective breath.

“Come,” their all-but-king motioned as he attempted to straighten his back, “for the weary never rest.”

Fleetwood pushed his chair away from the desk as the door opened fully, assembling himself again with his stick to the side in a posture of aloofness. The clerks, all in a fear, pulled back and allowed their master, Edmund Prideaux, to enter first, following behind him like shadows. The Attorney General’s eyes, always narrowed, scanned the scene. “Am I mistaken, or is this council begun without legal direction?”

Cromwell did not turn nor greet him except to respond, “You are mistaken in thinking law precedes Providence, for scripture tells us ‘The lot is cast into the lap; but the whole disposing thereof is of the Lord.’”

The clerks hesitated only a moment, then laid out satchels and bundles with practiced speed. Prideaux removed his gloves and took in Fleetwood with a tight nod.

“You’ve not had your morning readings,” he said, busying himself with the shuffle of papers. “Shall I proceed with the bulletin from the Lords brought by courier an hour ago? I’ve another from the Council of War.”

Cromwell gestured to the table without answering.

Prideaux approached with various pieces of correspondence when he noticed the parchment from Parliament still unfurled under Cromwell’s hand. Its seal was known. Its meaning, plain.

“I see the crown offer has not been dismissed.”

“Nor accepted,” said Cromwell.

“Delay is a form of acceptance,” Prideaux replied. “The nation waits.”

Fleetwood said flippantly, “The militia waits as well.”

Prideaux’s head turned with audible stiffness. “Your opinion is noted, my lord Deputy.”

The room bristled.

Prideaux continued, “You’ll not call this a Commonwealth if a man’s sons are named for succession. That is monarchy. If that is what you want, Lord Protector, say it plain. Otherwise, let this crown rest where it belongs: in the dust.”

Cromwell stared down at the offered throne.

“I remember such dust,” he said. “It was on the boots of every man who fought at Naseby. It was on the brow of the king when we took him at Oxford. And it was on the floor of the chamber when we cleared it.”

There was a pause, in which Charles offered, “Where Guy Fawkes failed, you succeeded, my lord.”

Cromwell looked up sharply. “Your meaning?

“He tried to clear the House with powder,” Fleetwood continued. “You did it with force of will. And unlike him, you succeeded. So I ask, is this what we fought for? To crown the cleaner?”

A silence fell so wide it seemed the fire had grown quieter.

Cromwell looked from one man to the other, then called, not loudly, but with full intent:

“Send in the first petitioner.”

The high clerk jumped, then with a glance at Prideaux moved toward the door.

Fleetwood frowned. “You’ve an audience?”

“I do.”

“With whom?”

“George Whitehead.”

Prideaux scoffed, but Cromwell cut him off. “A man I saw imprisoned for preaching, and released by your recommendation, Charles. You admired his bearing. Now I would hear his mind.”

“He is not of the Council,” Prideaux protested.

“Nor of this world, so it seems.” Cromwell mused.

A moment later, the door opened again, without formality. George Whitehead, looking far older than his twenty years, entered the room. He was dressed simply in a plain coat that bore rain marks near the hem. He did not bow.

“I greet thee in that life,” he said, “which brings all things to the Light.”

Fleetwood said nothing. Prideaux took a breath as if to object, then stopped.

Cromwell studied Whitehead with an intensity usually reserved for military briefings.

“You know why I have allowed you to come and beg further for your friends.”

Whitehead nodded. “I beg for all who are imprisoned and treated cruelly for the way in which they serve almighty God. But as to the reason thou hast allowed me the privilege…yes, I do know.”

The Lord Protector gestured toward the document. “Shall I read you the key parts?”

George shook his head. “All England knows the key parts, and these I have prayerfully considered insomuch as thou wouldst ask my thoughts on the matter.”

Prideaux, “It is amazing that you find the time, since you have turned grocer now.”

Calmly, the Quaker replied to the Attorney General, “Like the apostle Paul, I work to minister and minister whilst working.” He then turned his attention to Cromwell and offered, “Thou inhabits a throne, but the seat is temporary. Not because the Parliament offers another, but because all seats on earth pass away. I am come not to warn, but to remind. That men may bow before crowns, but the Lord requires obedience.”

Prideaux broke in: “You, sir, must believe you’re in a theology hall. We hardly need a boy to teach us what is already well known.”

Cromwell silenced him with a raised hand. “Go on.”

Whitehead stepped forward, slowly.

“I saw men beaten for speaking. I saw women locked away for kneeling. I saw chains on the young, and silence placed over the mouths of those who would sing. The law thou hast upheld in part—thou must uphold in full. If thou wouldst reign, then reign in mercy. If thou wilt rule, then rule with Light. But if thou accept the name of king, know that the people will expect a king’s justice.”

Cromwell allowed that sentiment to linger, until Charles asked carefully, “You think the title means the man is changed?”

Whitehead turned to him. “I think titles bind men in ways the Lord does not.”

The Lord Protector stood. He looked once more at the parchment. Then he folded it. Once. Twice. A third time. He placed it back in the drawer, shut it, and turned the key.

“I thank you,” he said to Whitehead.

“And what shall I tell those yet in prison?” asked the Quaker.

“That I have not forgotten them,” said Cromwell. “Nor the Light they follow.”

Whitehead bowed his head once—not to Cromwell, but to give brief thanks to God—and left.

The fire crackled again.

Prideaux looked disgusted. “A tradesman rebukes the Protector, and we thank him for it.”

The Protector nodded and picked up the tin. Ice cold. He debated whether to wake the steward that he might heat it up again, then turned to England’s solicitor. “The tradesman reminded me I am not immortal.”

“Then name thine heir,” snapped Prideaux. “Or accept the crown and be done with it.”

“I shall do neither.”

Fleetwood blinked. “Then what will you do?”

Cromwell meditated on his brew, holding the tin pot as though it weighed more than iron.

“I will reign while God wills it, and leave the rest to those who have not yet forgotten the cost of tyranny.” He winced and drank the coffee down cold. Beyond him, beyond the windows, the sky flushed pink with dawn. Yet heavy gray clouds bringing more dreaded rain boiled in the distance.

Iron and Ink

April, 1657

The farmer’s shed had been empty the better part of a year, its timber walls drawn tight against the hard frosts of winter. It was said every year was worse than the last and this one had been no exception. England was not the same as it had been before, in any time the older generation could remember. They blamed God, or the religious upheaval that called everything that was known previously into question.

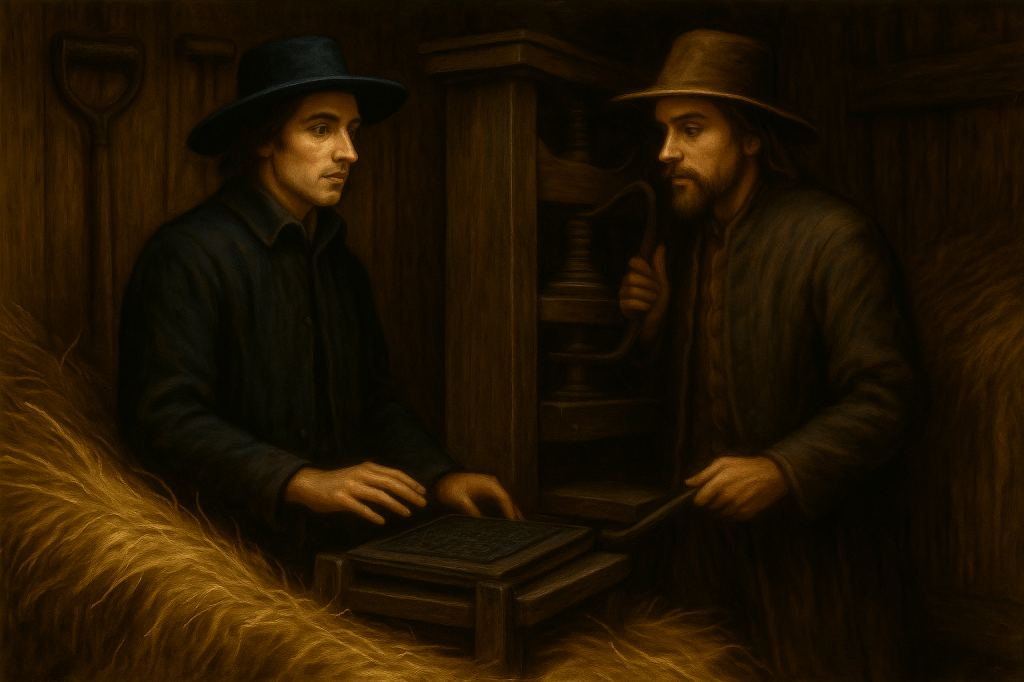

Now, though the storms had eased, the air yet held a tight chill. George Whitehead worked the latch and at last the door yielded with a reluctant groan. He stepped in first, lantern lifted. Again the hard cold greeted him, creeping up from the packed earth floor. A draught of April air chased him, and entering just after him, Stephen Crisp pressed the door closed with his shoulder.

Crisp was almost a decade older than George at twenty-nine, though only converted by James Parnell two years prior, just before the boy had journeyed to Cambridgeshire with young Tom. Now his eyes were hollow with lost sleep as he spent his nights burning oil or candle as they might be found, writing of the tragedies all around him and more too frequently reported from across the land.

He pulled a wood bar down to fasten the door, shutting out the faint glimmer of dawn behind them. Inside, the air smelled of oiled iron and old ink, chilled as a cellar. George had already stepped across the threshing floor and seemed overly interested in the bales of hay stacked against the back of the little cabin. Crisp squinted into the lantern’s glare and realized he was pulling at some kind of fabric.

With a great fall of loose straw, George dragged down a great canvas, which revealed underneath it a tallish yet compact machine, wrapped tightly in oilcloth. “Ah, they packed it away well,” he muttered with satisfaction. He cleared away still more silage that fell across the little press, testing a stiffened roller that yet contained traces of congealed ink. His fingers were stained already.

“Here it is,” he said, voice low, as if the walls themselves might betray them. He set the lantern on a rickety bench and brightened it. The circle of light fell upon the wooden press, crouched like a sleeping ox under its shroud. “She hath not been used in many months. After I was whipped on the street for pamphleteering and dragged away in chains, I scarce thought I should see it again.”

Stephen came nearer, brushing the hair from his face with ink-stained fingers. He was taller than George by half a head, the hollow of his cheeks and the darkness under his eyes betraying the nights spent keeping lists of the Friends’ sufferings.

“I have heard they searched desperately for it,” Stephen said. “Yet now I see how well-hidden it was. None would suspect a common farm shed.”

“Aye,” George murmured. He untied the cords that held up the canvas, and together they drew aside the big bulk of material. The press emerged in its entirety, black wood gleaming here and there where the polish had not dulled. A rusted tool lay across the bed. Mice had gnawed the corner of the frisket.

Stephen rested his hand on the platen as though visiting a holy relic. “Many words hast thou struck with this press.”

“More than I can reckon,” George said, smiling faintly. “And many more yet will be needed. The priests and magistrates will not cease their railings against us, nor their violence against Friends. So long as the Lord lendeth us breath, we must answer them.”

Stephen nodded, though he did not at once reply. He motioned for George to take one side and they moved it to the middle of the room, inspecting the worm-eaten edges. A brittle draft blew across the threshold, and the lantern flickered, shadows lurching on the rafters overhead.

“See how the drum locks here.” George gestured to the iron catch with a nod. “When the lever is thrown too fast, it shifts the teeth. You must ease it back, not force it forward.”

Stephen Crisp knelt beside him. His face was thin from nights awake, the new lines at his temples giving him age beyond his years. Beside him he had dropped a leather folio bulging with folded papers—his own notes of the trial, the torture and burial of James Parnell, the small unrecorded brutalities no pamphlet had yet told in full.

He watched as Whitehead lifted the drum clear of its socket and laid it on the bench.

“I am no printer,” Crisp murmured. “Yet I think I could learn the working of this.”

“Have we paper enough?” he asked.

“Three reams,” George said. “Hidden in the loft above. And ink in a cask by the wall. Thou wilt see—it hath settled and will need stirring.”

Stephen stooped, rummaging among a scattering of rags and tools. At last he found the iron rod they used to lift the platen when it stuck. He laid it across the bench, then straightened, rubbing his palm over his mouth.

“I cannot abide to think on it,” he said suddenly. His voice dropped to a hoarse whisper. “That he should come to such an end. That none would heed his youth, nor his frailty. I think of him each day.”

George looked up, meeting the younger man’s gaze. “James?”

“Aye,” Stephen said. “He was but a boy and not strong.”

“He was the strongest of all of us.”

“Yes, I see what you mean. Yet he was not blessed with a strong body. Rickets, likely. I have seen others like him, though none so brave.”

George lowered his eyes. “I remember when he came out of the North, all thin limbs and sharp speech, as though God Himself had lit a flame in his marrow.”

“When I first heard him I thought he spake as though angels gave him utterance,” Stephen whispered. “And yet they would have it he was a vagabond, a pestilence, an enemy of all order. That jailer’s wife, wicked Jezebel, what she did to him—” He broke off, breath shaking.

“Tell it, if it easeth thy spirit,” George said.

Stephen swallowed. “I have writ it all, but I would speak it plain that none forget.” He drew nearer to the lantern, his face stark in its glow. “She beat him, George. Beat him with her own hands, and bade her servant strike him also. She gave his food to other prisoners, lest he keep his strength. When Friends brought a bed, she denied it. He was forced to lie on the stones.”

George closed his eyes a moment. “I know it.”

“Yet I did not know all,” Stephen went on, voice low and fierce. “Our friend turnkey tells that when he fell—when that cursed rope slipped—his head struck the floor. So wounded in the skull, and all along the ribs, they took him for dead. The jailer’s wife had him cast in a worse pit—a small cave lower down, where the walls weep even in dry weather.”

Whitehead exhaled in pain. “Aye. They did all they could to finish what the rope began.” He looked as if he wanted to yell, to hit something, to run. Instead he prayed. And after his amen yet muttered, “I would have taken his place.” This though he well knew the same offer had been made and denied for his own sentence.

Stephen shook his head sadly. “Friends petitioned—good men and women, willing to lie in his stead that he might be brought to a bed and given care. Denied, all of them, and the jailer the angrier for it.”

A silence fell between them, broken only by the keen of the wind at the eaves. For a moment, neither moved. The little press seemed a greater thing—more an instrument of witness than any pulpit. Crisp touched the handle as though it were a holy relic.

Then George drew in a slow breath and turned his attention to the pot of lampblack, placing it up on the shelf. Outside, the low fields spread to the edge of the orchard, silvered with dew. A single cockerel was picking through the straw near the gate. No rain now, only a dampness that never lifted. “He shall not be forgotten,” he said. “Thy words, and mine, and the words of all Friends, will stand against their cruelty. We shall print every account, every testimony.” He turned to the printer again, picking at the remaining bits of hay and chaff. “This part of it, a simple trade, we only need the hands. Once the paper is set, the rest is only discipline.”

Crisp looked up at him nodding, though his eyes doubtful. He opened the folio and drew out a sheaf of rough notes, names and dates scrawled across them in an impatient hand. “If this be my work, then I would have thee show me every inch of the press. For I will not let it be idle.” He looked at the page, and too many more of them in his hands. “I only pray they will read it. That someone with the power to command mercy will not just see and hear, but take an action against England’s cruelty.”

George lifted the frisket and examine the frame. “This is the frisket, which lays atop the paper. This corner was splintered where I forced the iron pin in my haste. It must be mended, else the sheets will slip. There was another dowel…” He went to the tool shelf near the door and reached to the back of it, pulling forth a small piece of rounded wood. As he struggled to work it into place, he spoke in a low tone. “Stephen—I can but speak where I am called to speak. To print these words and pray for ears to hear and eyes to see.”

He stopped pressing the piece in frustration and stepped back, eyes closed for a moment as he took a deep breath. “Friend…tell me, for in you I find one that does not expect so much of me. They think me another George Fox, but let me speak as a simple man of faith…dost thou ever doubt? That we are not equal to the burden the Light has given us?”

Stephen paused, then looked up to meet his young companion’s eyes across the lantern’s light. “Yes. I have doubted. Many times. When James lay dying, I asked the Lord why He should permit such darkness. But I have found no peace in silence. Only in witness.”

“Aye,” George said. His face lit with an idea and he returned to the shelf. He quickly located a mallet, which he used to set the dowel in its place. “It is true—better to speak and be scourged than hold thy peace and have no answer to thy conscience.” He lifted the frisket and seemed happy with its function.

“Now then, there are but few other pieces to know. This frame stretched with leather is the tympan where rests the paper. The duckbills mark the placement. We will press the paper through these tiny pins to hold it,” he said as he scraped old ink from the tympan. “Now, open the cask of ink just there and stir the ink. I will look to the type.”

Stephen unstopped the cask, and where there was a thought of ink before, now a sharp scent rose, bitter and familiar. “It looks to be ruined, Friend George.” He lifted it to show a muddy mass inside.

“Nay, stir it with a rod until it be fluid again.”

Stephen then began working the ink as George retrieved trays of movable type, half of it in disarray. Some letters had rusted to the case. Whitehead pried one free and held it up. “Here, feel it in thy hand.”

Crisp obediently held his hand open and looked at the metal piece.

“When you take hold of it, you must only touch its shoulders. Mind the face is clean. When thou setteth a line, think first of the shape. The shape will rule how it prints.”

Crisp weighed the piece of type as though it were heavier than lead.

“When I was in the Castle,” Whitehead went on, returning the piece to the tray “I dreamed we had a press as wide as a hay cart, and all England queued to read it. I woke and found the rats had eaten the sole of my boot.”

Crisp nearly smiled as he applied force to the ink. “A sign, perhaps.”

“Aye.” Whitehead reached for the next line of type. “A sign not to wait on visions, but to work with what hands we have.”

When the ink was ready, Whitehead began setting type as Crisp read lines from his folio.

“The title, George, all large letters. ‘A TRUE RELATION OF THE SUFFERINGS OF JAMES PARNELL’ and then the next line, ‘Written by One Who Knew Him.’”

They worked for some time until the wind rose and the latch rattled. Crisp glanced back, his shoulders tensed.

“They will come for thee again,” he said quietly. “If this is printed.”

“They may.”

“Then—” Stephen hesitated. “Then I should be the one to hand them out. I am the pamphleteer in this case.”

Whitehead shook his head. “Thou art worth more out here as my puller. Leave me to answer for the words.” He smiled ruefully, “My shoulders no longer like the work of the press.”

His companion looked up, hesitated, but could not help but ask. “Are they scarred, George.”

“Aye,” he nodded as he worked. “Pulling the rod will give me trouble this time, and that is the most important work, once the type is set and the ink laid.”

A silence spread between them. Crisp looked back to the folio, to the testimony that seemed too small to contain all he had seen.

In time, he set the words down. “These sentences are too hard. I must remember that young James is in Spirit now with our Lord.”

He rose and unlocked the door, stepping outside in the wind. The afternoon air moved through the shed like God’s breath.

Whitehead wiped his hands on a rag and followed. In the field, the cold was not sharp but endless, a damp cold that sank through wool and into the bones. He stood there a long moment, as if reminding himself the world was still here—still turning, still worth claiming.

“Stephen,” he called over his shoulder, “Come and look.”

Crisp joined him at the top of a hill.

Below the orchard, the pasture was greening despite the season’s reluctance. A few lambs moved among the brambles, pale shapes against the sodden earth. No rain fell. No sun broke the clouds. It was simply April—raw, unsettled, alive.

“That is how I feel,” Crisp said after a time. “Like that pasture. No warmth yet. Only a promise of it.”

Whitehead nodded. “Better a promise than no hope at all.”

They went back inside.

Whitehead fitted the drum back into place, showing how the catch locked when it was turned gently. Crisp followed every movement, committing it to memory.

An hour later, the press was clean and ready. Whitehead closed the lid over the inkstone and laid the first sheet of Crisp’s testimony across the platen.

“Go on,” he said.

Crisp took hold of the lever. He drew a slow breath.

“For James,” he murmured.

“For all of them,” Whitehead said.

The lever came down. The first impression set its mark.

Hours passed, and George was right. The greatest work was in the pulling. He set page after page on the tympan, while Stephen pulled the lever to press the inked letters onto the paper. In time the lantern burned low. Stephen stepped back, wiping the sweat from his brow.

“Let us breathe the air again,” he said. “My heart is heavy, and I would see those fields once more before the sun sets.”

George nodded, following him to the door. “I have enjoyed many sunsets here, and missed them while I was away.

They stepped out into the gray light that in the west gave way to a rosy hew. Stephen gloried in the heavens, drawing in a long breath that yet chilled his lungs. “I dream of a day when men will cease to imprison and kill for want of conformity. May God allow us to see it.”

“I think,” George said slowly, “that the violence of men is like a flood—swift to rise, but it cannot remain forever. If we stand in the Light, it will abate. I have seen Cromwell’s heart moved to mercy, though he doth wrestle with his pride and power.”

Stephen studied him as twilight crept behind them. “Thou spake with him again?”

“Aye,” George said, a weary smile tugging at his mouth. “He would know our mind on this business of the crown.” He looked to Stephen, who well hid a burning curiosity to know more. “I told him plain: If thou wilt reign, then reign in mercy. If thou rulest, then rule with Light. But if thou accept the name of king, know that the people will expect a king’s justice.”

His listener looked away across the fields, where the furrows gleamed with the last light of day. “He cleared the throne and Parliament as none before him, not even that papist plotter Guy Fawkes. And yet the power remains, gathering in his hand like a snare.”

“Aye,” George said softly. “And so must we bear witness, that it not be used against the innocent.”

The wind touched their faces, searching and cold. Presently George turned back to the shed, lifting the latch again. “Come—let us finish what is needful. I would see these sheets struck ere the week is out.” Stephen followed. Inside, the shadows waited, but they no longer seemed so deep. Together, they set their hands to work.

A Year’s Lament

In Cambridge, the cold that had clung to the lanes like a curse lifted just enough to let the stink of the River Cam drift in among the alleys. Duffy had told himself the warming air would lessen the ache in his bones, but no balm touched the hollow in his chest where Bess had once touched his life. He had not washed the mug she last drank from. It lay on the shelf by his door, a grey film at the bottom where the cider had settled, thickening to a crust.

Life had settled into rote; Pip up in the early morn to bake his wares, then off to the bridge to sell them. He wakened more slowly each day, his blood more full of the drink of the night before. Without washing he set foot across the city to Castle Hill, passing the market without thought or recognition. His coat hung from one shoulder, and his eyes had the fog of a man unmoored. No one called his name. No one dared.

The street hawkers shouted it first—gravel-voiced boys with ink-stained fingers and wrinkled doublets, crying out at the gates of city yards and market lanes.

“Lord Protector refuses the crown!” They held aloft the broadsheets, enjoying a brisk business. “Lord Protector refuses the crown!”

In his long-held habit of misery, Duffy heard the words but did not stop to read or discuss. He passed beneath trees budding shyly in April’s chill, the pale sky stretched wide like bleached cloth. His boots made no sound on the damp earth of the alleys. Only the jingle of his iron ring of keys range against the stone walls.

Months passed in the same way, as Cambridge roiled in a tepid heat that yet drew forth a human stench. Within Castle Hill, a fight broke out in the prison yard—two cartmen brawling over stolen shoes—but Duffy sat on a bench beneath the overhang, one hand dangling over the side, holding a pewter cup.

Thresher waded in, shouting, striking with his baton. “Ye’ll mind the peace, or I’ll mind it for thee!”

Blood spattered the stone wall. Duffy didn’t flinch.

Thresher approached him, chest heaving.

“What good are thee now, Duffy? Sittin’ there like a tavern ghost while this place turns to rot?”

The turnkey swirled the last inch of sour beer in his cup and muttered, “I was never your keeper, Thresh…yet I see now ye were mine.”

It was too warm for the large man to argue. He left Duffy to his silence, but vowed to find a replacement. A man who drank only cider, if he had his way.

By the time the cold winds returned, whirling autumn’s leaves helplessly in the air, Pip had become a member of the Blakeling household; cleaned and dressed in proper garb by Minta. Yet he could not stay, for his old master had heard the rumors of his boy not dead at all but thriving. Came the day when he stood between the two Quakers—clean-faced, solemn, dressed in a russet coat two sizes too large, clutching a satchel with both hands.

Minta had dragged Duffy to the coaching inn to see the boy down the road. The drunkard listened with dull eyes as she said, “He’s taken to John’s more civilized ways well enough, and they’ve secured him a spot in Shoreditch. An honest baker will train him to proper trade.”

He leaned back against the side of the building, unsteady even as Pip climbed atop the coach with newfound confidence. Taking his seat with the cheaper fares, the young man now almost fifteen waved them all goodbye. He cast a cautious glance now and then at Duffy, or the man that was him once. He in return looked up through hair grown wild.

“The boy’ll not like Shoreditch,” Duffy muttered.

“He’ll like food,” John retorted firmly. “He’ll like not spending his life as servant to Castle Hill.”

Minta approached the coach and blew Pip a kiss.

“Will you miss me?” he asked her.

She smiled gently. “Aye, lad, but ye have a lifetime to come back and see us.”

The coach lurched and he waved at them all again, continuing as they rattled off down the lane. Duffy watched without moving until the dust settled.

Later as winter’s frost cracked the edges of the puddles in the courtyard, his former employer threw open the door of his home. Duffy lay huddled on his cot, which he’d pulled up close to a weak flame in the hearth. He’d bundled himself in a militia cloak turned to rags, smelling of sweat and ale and the burnt fat of the jail’s kitchen, where he begged scraps on days too cold to stand.

Thresher stood over him, red-faced and angry.

“Rumor says the boy lives,” he growled. “Ye thought to keep him from me!” He kicked the cot, breaking the legs at one end. “He’s mine. I raised him as me own. And I’ll not have him hiding behind apprenticeships!”

Duffy rolled to the floor with a groan. “He’s not your ox, Thresher.”

The jailer kicked him in his side. “He’s not yours either, ye old sot. And if ye won’t answer, then ye’ll not lie here in the turnkey’s house!”

The door slammed, then opened an hour later as two large men came to turn Duffy out. He stood reeling in the street as heavy flakes quickly covered his shoulders. They barred the door and left him there, his few possessions at his feet, and the snow muffling every sound but the groan of timber houses.

Cold’s grip held fast in the early months of 1658, and Duffy was yet without a home as the first thaw stirred. Spring crept forward with sluggish steps, its promised warmth a mere murmur against the stubborn chill, as though it hesitated to wake the world from the frosty hold of the worst winter anyone could remember. The trees, tardy in their blooming, stood bare far into the season, while the chill sank deep into the city’s bones. Yet, in defiance of the lingering frost, the markets bustled early, their stalls braving the air as if in scorn.

Duffy staggered through Smithfield, some twenty miles safe from Castle Hill. He had become a local character; hungover, silent, carrying only the cup from which Bess had drunk her last. He’d become accustomed to the overwhelming smell of ink and slaughter that filled the square by the end of every day.

He drank without remembering what his cup held. Wine, beer, the dregs of some black bottle passed to him by a cooper on a dare. He remembered none of it, only the warmth it brought his stomach and the hush to his grief.

In his mind, Bess still stood at his table, wiping flour off her apron with a careless hand, Pip at her side. Tom he imagined laboring in the kitchen at the county correction house, carving his bones to buy freedom. Parnell, the weakling with fiery voice, still lived in some dark wall at a prison far away.

But they were gone, all of them. He drank to the ghosts, drank for his losses, drank for fill against the emptiness that was never quenched.

Soon he could pass his days unobserved in the woods beyond town. He returned to the square only to beg a penny and buy more beer. By August, the air was thick with rumor again. The Lord Protector’s ailments were unto death now. Some claimed malaria, others the judgment of God. Still others said exhaustion, proud of the man who had labored tirelessly for those who believed in his religion. A few whispered poison for the same reasons.

Duffy did not care to hear the arguments, preferring instead to drift like a sailboat with a torn mast, bumping up against taverns, sleeping now and then in a heap of new-mown straw, returning to Cambridge only when chill winds drove him back to the one place he might find a welcome corner. He thought he’d try the servant door at Blakeling’s house, to see whether a ghost might answer his knock.

All Hallow’s Eve found him crossing the town square with ragged steps. A pantomime on the corner had lured the children of those brave enough to suppose they might celebrate this night without fear of retribution, for the city once ruled beneath an iron fist now tottered between various hands.

A voice from the distant past reached his ears, for Lark was there, now in shining new attire, singing a nonsense tune while a little dog at his side danced and begged scraps.

“What shall we say of our dear departed, and what do we say to the next? For our Lord Protector is dead—long live…who?” He asked the children who were listening with delight. “Long live the next Lord Protector?”

As a chorus they shouted and shook their heads, “Nooooooooo!”

Lark laughed to himself and spun in a circle, arms wide.

Parents came close but on hearing the dangerous tune, pulled their children away. The bygone minstrel looked up, espying one approaching who was not quite a stranger. His partner had already stepped forward, eyes narrowed as he looked to see what might be taken from his unsteady prey.

“Fancy a game, friend? Deadman’s Chance,” he said, and with a wide dramatic gesture pulled a colorful pair of dice from a soft leather pouch.

Cress. He too had bettered his clothes, topped by a warm cloak to ward off the chills of the night. He threw, and the dice clicked upon the cobbles like frozen teeth. One landed at the feet of the visitor, who stared at it unsteadily, before making a rather large effort to get down on one knee and pick it up.

“Hey now,” said Lark, catching hold of his partner’s arm. “I know him. Or did.” He peered closer as the drunk lifted his head dizzily. The minstrel gasped. “Ain’t that Duffy?”

“Don’t be daft,” muttered Cress. “It ain’t. Can’t be the same man.”

But the drunk was preoccupied, rolling the die in his palm.

He stared at the grooves—etched not with letters, but tiny scenes. A mouse. A tree. A boat. A horse.

He knew the hand that carved it.

“Where’d ye get this?” he asked thickly.

Cress, sensing profit, smiled. “India. Carved by a mystic.” He knelt in with a conspiratorial whisper. “There is magic in it.” Duffy straightened slowly. His knees cracked. His hand closed over the die.

“I’ll not pay,” he said.

“It’s not for sale,” said Cress too quickly. “I was only saying where it came from.”

Lark leaned closer, frowning. “He’s not what he was, but this is the jailer who came to see the boy a year ago.”

Cress laughed, then spat at Duffy’s feet. “Him? This is the boy’s Lord Protector? Aye, you disappeared, didn’t you? Well he’s our friend now. We sell his wares to help him.”

Duffy turned on them. “To help yourselves, I see.”

“We’re like fathers to him,” said Lark, shrugging. “And you are dead. All but.”

Duffy tucked the die into his pocket. He felt it burn there. The two reprobates tried to overtake him, but a monstrous strength had returned to his arms. He pushed them both to the ground, standing over them, wavering yet suddenly wakening as well.

He did not go to the Blakelings. Suddenly sober, he found a haystack and sat beneath the moon with the dice; contemplating the one against the other, and the growth of the carver who had made them. A dawning realization overtook him. Tom was not the boy he had been at that age, nor even like his Quaker friends, the Georges. Nor even like young James Parnell.

Tom was not weak—he was like Pip, a boy who needed someone to protect him from the snares of the brutes who live to take advantage of anyone with a kind heart. And that were Tom. He nodded to himself as he regarded the pair of dice. Yes, he saw it now, just as Bess had told him a thousand times. A boy with a kind heart needs a father-like man to protect ‘im. Aye, that were Tom.