It’s possible my tendency to geek out over historic trivia has overwhelmed my story. So in the interest of more “show don’t tell” I have developed this scene to replace the transcript from the list of Quaker sufferings at the beginning of my story. Dedicating this to my great-niece and fan of historic fiction, Serenity.

The fog had lingered through the night and continued through morning, so that the streets were a slurry of mud and slime. Though June was nearly spent, the air stubbornly held an icy chill as it had for some time now. Only the oldest Englanders could recall a time when winter kept to its own season.

Tom shuddered, his little hands pulling at a worn woolen coverlet that served as his cloak. He shuffled along the edge of King’s Parade, noting how his bare feet squelched on the cold wet stones. He had learned to keep his ears open and stay in the shadows, though he didn’t quite know what he feared most—the chill in his bones or the bustle of the scholars in their black robes.

Cambridge was known to draw teens from from good families intended to study for a religious post that likely had already been set aside to secure their futures. To Tom it seemed these older boys took pleasure in adding to his torment now that he had neither father nor mother to protect him.

The bells of St Mary’s rang across the sky, their peals muffled by the dense mist. He tilted his head, straining to catch any pattern, any meaning in the tolling that might guide him past the throng. Were they off to chapel or back to classes?

At nine years old, Tom Lightfoot had seen more grief than any boy ought: mother long dead and leaving no memory of herself behind, and a year ago his father taken by black lung. Since then he’d been shuffled from one miserable orphanage to another, leaving him only dismal memories like faded candlelight.

As he’d done before, he’d run from the latest house—not much more than a work-house—rather than join his brethren in the mines. Now with feet slick and mud-caked, he watched the square come alive with the presence of strangers. Two women moved with a quiet determination. The scholars took note with a rise in their scoffing tones that made him stop and press against a barrel, his small frame shivering not only from the cold but from anticipation of what was to come next. He hated the brutal spectacles that so many seemed to enjoy.

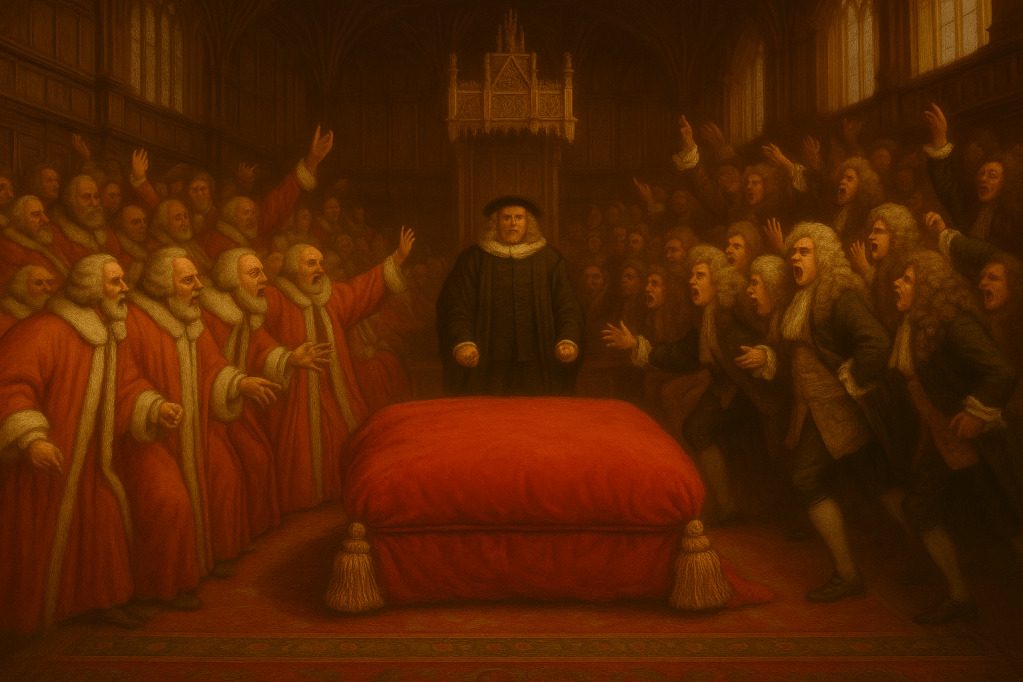

Mary Fisher, not yet thirty, with a gaze that held fire without flame, and Elizabeth Williams, older, steady, her greyed hair tucked beneath a bonnet, threaded their way through the crowd. The air seemed to bend around them, fog curling past their skirts like smoke around a lantern. Tom crouched low to make himself invisible. His small heart thumped, loud in his chest, each step of the women over the stones seeming to echo like a drumbeat in his ears.

The scholars on their side of the square clustered in stiff black robes with great wide collars. They spoke amongst themselves in clipped, precise tones. The boy could not follow every word, but the sense of authority, of hierarchy, struck him like cold iron.

One boy, tall with a hawkish nose, said something about the “necessary guidance” the clergy must provide “to an uneducated populace unable to discern the true will of the Lord.” Another nodded, adding that those who had not studied Scripture properly must be shown the way, else chaos would descend. Tom’s ears caught the words and sifted them into fragments: uneducated people like himself, who could not understand beyond their station. Each phrase sounded like a verdict, like a bell toll for the common folk, and with a sinking feeling of despair he pressed his face further into the folds of his blanket.

As the women approached the scholars crowed at them, for it was obvious from their attire that they belonged to a new sect, the “plain” folk who refused all adornment. Their heads were covered instead with simple white caps devoid of embroidery or trim. One of the young men asked loudly, “How many Gods do you suppose there are, oh wise Children of the Light?”

The younger woman responded with a voice clear but not loud, unwavering in its confidence. “But one. Yet thou hast many gods and are ignorant of the true God.” Tom’s chest tightened in awe. The elder woman leaned close to her companion, her own voice a steady counterpoint. “And those who cannot read must not be left in ignorance. Our charge is to lift them toward Light, even if the world would see them in shadow.”

Tom did not understand all they said, being a boy of narrow streets, but he understood enough: they spoke of hope, of defiance, of justice, in a language that warmed something deep within. The robed young men were in a fury—for none called them ‘thou’ except their mothers—and murmured among themselves in voices sharp and condescending, as though the women’s courage were a child’s trick. Tom’s small fists curled at his sides. If only he could speak, he would have shouted at them to hold their tongues, to listen.

A sudden clatter—the gate at the edge of the square, or perhaps the falling of a barrel—made him flinch. The fog swirled and shifted, and for a moment, the world seemed magical and terrible all at once. Tom’s ears strained, and just then there was a great metal clang as the iron end of a constable’s staff slammed hard against the stone path. Syllables of the scholars’ speech blended with the clamor of the square as hawkers and shopkeepers joined the edges of the crowd to see what might happen next.

“Constable!” shouted the hawk-nosed teen. “These women are preaching in the square, in spite of laws against such yammering.” What laws these might be they hardly knew, but assumption is ninety percent of the game.

Another shouted, “Make a complaint to the mayor! Pickering will want to hear about this!”

The constable stepped forward, a storm brewing in his brows as he approached the two women. The crowd parted like a river, and Tom’s stomach twisted. He could imagine the sharp, pointing fingers of the learned young men who would enforce order, and the sharp glistening eyes of enforcement that turned upon the women. “What’s this? Who are ye that ye come ‘ere to our peaceful town, eh?”

The elder stepped forward defiantly and stated, “Our names are written in the Book of Life.”

“Wha?? Where ye from then? And where’d ye stay the night last?”

She would not bend, but responded only, “We are strangers. We know not where we huddled for a rest beside the road overnight. Under a tree somewhere. But the Light has drawn us nigh.”

“The Light wants to know what’s yer husbands’ names is,” returned the constable, who grinned at the crowd now tittering along with the scholars. “I’ll warrant they’ll whip ye both if they have some sense.”

“We have no husband but Him whom we serve, Christ Jesus.”

With that he stepped forward and shoved the two, so that they nearly fell into the mud. “Right. Get on wi’ye. To Pickering ye’ll go.”

Then like a circus parade the crowd followed the constable with his victims as he prodded them onward with his stave. Tom kept to the back, so that by the time they were in the mayor’s office he was obliged to listen beneath a window full of local gawkers. They narrated what they supposed was being asked and answered.

“Aye, there he’s asked again who’s their ‘usbands.”

“Has she called the Mayor ‘thee’ yet? That’ll make him right angry, won’t it?”

And as if on cue there was a loud yell and a curse. Even Tom heard clearly the words from Mayor Pickering’s desk. “Whip them! Whip them until the blood runs down their bodies!”

The listeners stepped back in shock so that Tom could jump up to the window and catch a glimpse. Both women had crumpled down to their knees and seemed to be praying. He hoped Pickering might have pity now.

Instead he roared, “I need not your forgiveness! Get out of here both of you, and if I see you in Cambridge again I’ll see you die in prison!”

An official then cried out for the executioner, and soon the entire party was off again down the path to the gallows where there a well-used whipping post awaited its next guest. Guards tore the women’s cloaks from them and tied them, one to each side.

They held each other as they continued to pray—not for themselves, Tom noticed, but that God might forgive the executioner. This only served to incite his fury all the more. His face worked to such an extent that the boy hid himself again, for he feared what might happen next.

The first crack of leather made him jump. He hid his eyes, but the sound was enough to mark him. Each whip across their backs was a thud in his chest, each prayerful word they uttered a cry through his bones. The fog, the mud, the bells—all blended into a haze of terror and awe. He dared not move. He dared not breathe. And yet he listened.

Through the haze, he imagined the rhythm of the lashes, the snap of cruelty. Then the exhalation of courage came…in the form of a song. To the surprise of the crowd, both women were singing:

“The Lord be blessed, the Lord be praised, who hath thus honored us and strengthened us thus to suffer for his Name’s sake.”

The townspeople pressed closer and exclaimed to each other. Tom could not understand what it all meant. For him in that moment, the cruelty of the world was revealed in full: power, authority, law, and the tiny resistance of the faithful. He did not see everything; he had hidden his eyes. But each sound, each gasp, each sharp word burned into memory.

When it was done, the women were led away, their clothing torn and stained, the street slick with muck now mixed with their blood. Tom crawled from his hiding place and followed as best he could, even now afraid of being seen. Yet he heard the women still speaking calmly and without fear, as if they were on their way to market. They encouraged all who would listen to fear God, not man. As they neared the city gate, Tom ran up along the wall to see them better.

A well-dressed shopkeeper called out, “They are madwomen! Look how they sing psalms instead of weeping.”

At this Elizabeth Williams stopped and said, “We are blessed to suffer for His name’s sake. And understand—this is but the beginning of the sufferings of the people of God.”

The constable had heard enough. He pushed the two roughly outside the gate and into the mud. Without another glance at them he stomped over to the guard and explained the mayor’s commandment—the two were never to enter Cambridge again.

Tom now reached the top of the gate and watched from above as the women helped each other stand. He could see they were shaking as they stepped to the side of the road to straighten their torn clothes. Just then, a shadowy figure above the parapet opposite him threw down a bundle. Mary quickly stepped over and picked it up before the guard might notice. When the two lifted their faces in thanks, there was none to bless. They turned then and saw Tom, who gave them a shy wave before ducking down below the parapet.

Someone had helped them!

He sat, hugging his knees with his eyes closed, thinking of his own life. From his earliest years he had been resigned to running errands and hauling coal with his father, then being torn from that life he had slept on the cold floors of the work-houses they called orphanages, weeping over his meager crust of daily bread. And now he lacked even that, for in his pocket was a tiny bite of moldy cheese found in a refuse pile. Yet by comparison he was rich, compared to the women he’d just seen.

Here above the guttering lamplight he’d glimpsed courage, faith, and the possibility of choice. That day, he realized, the world was wider than his small life, and cruelty could be met with something even greater than defiance.

He did not know it then, but the lash that fell on their backs had marked him too. The sound of leather against flesh, the cry of a soul standing against authority, the smell of damp and fear—all had etched themselves into his memory. And in that marking, something began to stir—a sense that when the time came, he would have to choose between obedience and conscience, between survival and doing what he knew to be right.