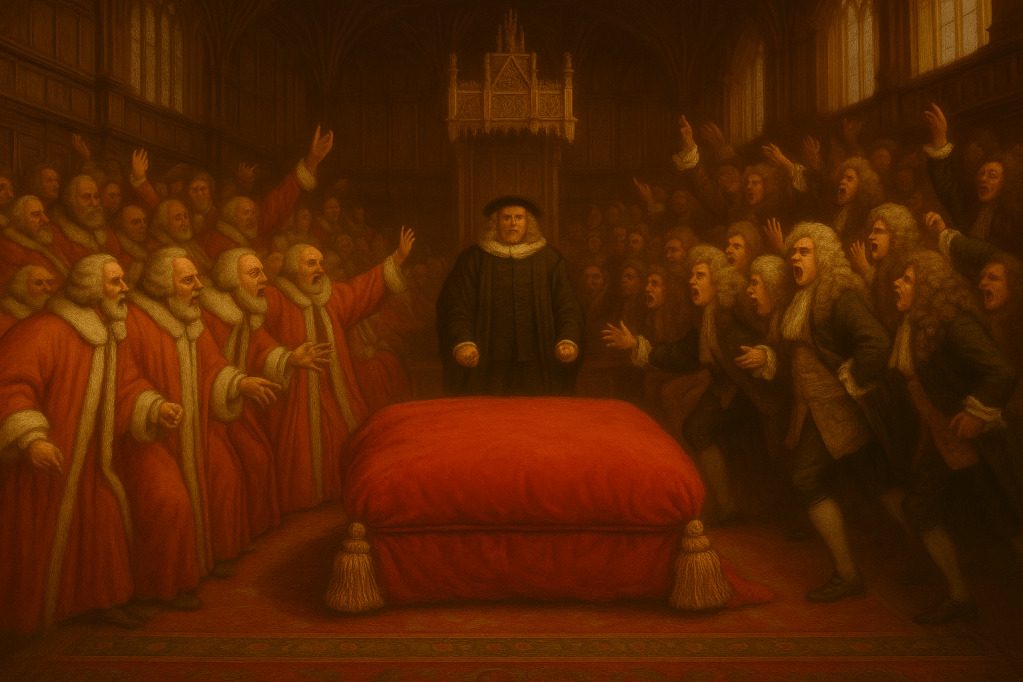

Having finished with my introduction of Charles II and his courtiers, I have moved on to another research-heavy chapter: how the punishments for Quakers were ramped up by the House of Lords in spite of the King’s desire for tolerance.

It has taken many hours of inquiry in the form of discussions with both Google and ChatGPT-5 about what the chamber looked like at the time, and the characters involved on both sides of the aisle, and of course a lot of writing and rewriting to get from the starting point of the King’s request to the ending legislation that created what amounted to a police state throughout England. The Quaker Act punished severely any perceived religious meeting of five or more people, and suddenly any thief or drunkard could lessen their fines by turning someone in.

It helped that Eddie happened to watch a meeting of the House of Lords recently. I was shocked at the yelling back and forth and how it appeared to me like an undisciplined high school debate, sprinkled with calls of “Here-here!” and a great deal of booing and even the stomping of feet. So that had to be worked in as well.

All of which brings to mind, as does every chapter and sometimes individual paragraphs, the similarities between those times and these. Turbulence. The will of the people, however divided they may be. The will of lawmakers. The will of the heads of state. How can there be peace on earth when there is a continual sense of dissatisfaction with the status quo and a desire to improve juxtaposed against the wealthy protecting their funds?

As Christians, we are taught by the Bible to continually seek to be more like Jesus. To forgive seventy times seven, to love the unlovable including ourselves, to refrain from even calling anyone an idiot because in doing so we destroy them as a person. But there is also a desire within humanity for better, for more, for improvement of our personal circumstances. All of that is the individual stuff. Layer over that the call to improve our church body. And over that the desire of the clergy should they oppose us.

And then this is where my eyes cross, because as a free person in a free country, I have always had the ability to just leave if I wanted. Imagine if your church was assigned, and the clerics above you were assigned, and you could not “wipe the dust from your feet” if you disagreed with them. I have said before that money was the issue and if you follow the money it pretty much stinks to see how the wealthy bishops used it. And this week I discovered how the bishops were squandering the hard-earned tithes of the people, by doling out livings to any who would support them in their careers.

As a result of their legislation, there was a period when Quakers who threatened this way of existence were exiled to plantations in the American Colonies or the Indies.

Once I complete my work on this chapter, the next one examines this police state and how even the mercy of the King could not save his subjects. And how some people cheered and others felt justice had been done. Sound like anything happening in our world today?

I grew up with a generation of elders who had witnessed the worst in people, and who were proud to say that we, the people of the United States, had helped put an end to hatred and antisemitism. Imagine my horror to find that my generation should actually bear witness to its return. And that Christians of all kinds could have targets upon our heads.

I’m not so sure this book is about Quakers or even about Spirit-filled youth. As God leads me through the story, it seems to be about how a society can be divided against itself and one citizen can turn against another, both believing they are in the right. And let us not forget the money that stokes the divisions.

Thoughts on the matter? Leave a comment.